Fundamental Cap Rate Analysis: The Flex Stay Example

How should novel concepts like flex stay apartments be priced? A deep dive into fundamental cap rate analysis

Today’s Thesis Driven is a guest letter from Roman Pedan, Founder & CEO of Kasa, a flex stay apartment operator. It proposes a cap rate framework for novel categories of real estate using flex stay apartments as an example.

Having sat in a real estate private equity investment seat for part of my career, I know the importance of exit cap rates to real estate valuation models. It seems that discussion around cap rates has only intensified of late, as the cost of debt continues to climb (as of writing this, the 10-year treasury sits at 4.6%, up from 3.6% only 6 months prior).

Despite all the focus on exit cap rates, my experience as CEO and Founder of Kasa, a leading flex furnished rental operator, has shown me that there is still confusion around how to value short-term rental income in a multifamily building. This letter offers a common-sense framework to arrive at a fundamental valuation metric for this emergent real estate asset class.

Background on Cap Rates

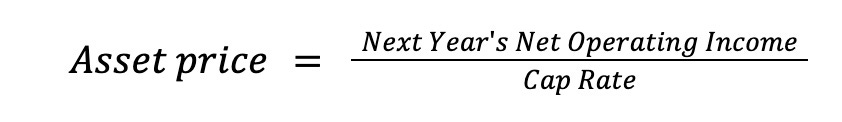

Capitalization rates (or cap rates) are widely considered one of the most important factors in valuing real estate assets across all sectors. In short, a cap rate calculates the expected annual current return on a real estate investment. It is calculated by dividing the recurring annual income of the asset (also known as the Net Operating Income or NOI) by the property’s price.

Said another way, you can calculate a property’s market price by dividing NOI by a market cap rate. The higher the cap rate, the higher the return on a given property relative to its price, and the lower the cap rate, the lower the return relative to its price. Properties with risky or volatile cash flows with low growth prospects typically sell for a higher cap rate (read: lower price), and properties with less risky cash flows and/or higher growth prospects sell for a price that reflects a lower cap rate (read: higher price).

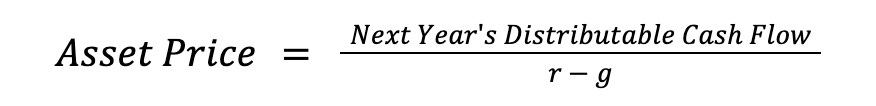

The derivation of a cap rate comes from the Gordon Growth model (also known as the dividend discount model). This formula also underpins how a stock—or really any security where dividends grow at a consistent rate for a perpetual period—is valued in finance.

P = stock price

D1 = value of next year’s dividend

r = unlevered discount rate or required rate of return for equity

g = constant growth rate into perpetuity

For real estate, the formula can be restated as:

where

r = the unlevered discount rate and

g = the expected growth of the distributable cash flows into perpetuity.

Together, r - g is the cap rate.

In most cases, we assume Net Operating Income (“NOI”) is the stand-in for distributable cash flow (although the merits of incorporating some measure of defensive capex can be debated) and r - g is the cap rate.

So in real estate,

Taken simply, this formula restates that cap rates should be higher when cash flow risk is higher and growth is lower, and vice-versa.

Real estate investors, naturally, hope to buy properties low and sell them high. Exit cap rates (also known as a terminal or reversionary cap rate) inform the sale price that an investor expects to achieve at the end of an investment, making it one of the most important assumptions a real estate investor makes. Reversionary value can represent as much as 70-80% of the value that an investment generates over a typical 5-year hold period. Real estate valuation models are highly sensitive to the exit cap rate; get the exit cap rate right and everything else wrong and you may still have a great investment. Do the reverse, and you might be looking at significant losses.

Cap Rates by Real Estate Sector

The first question aspiring real estate analysts are often asked during a technical real estate interview is to rank-order real estate asset classes by cap rate, from lowest to highest, and explain the reasoning behind the order.

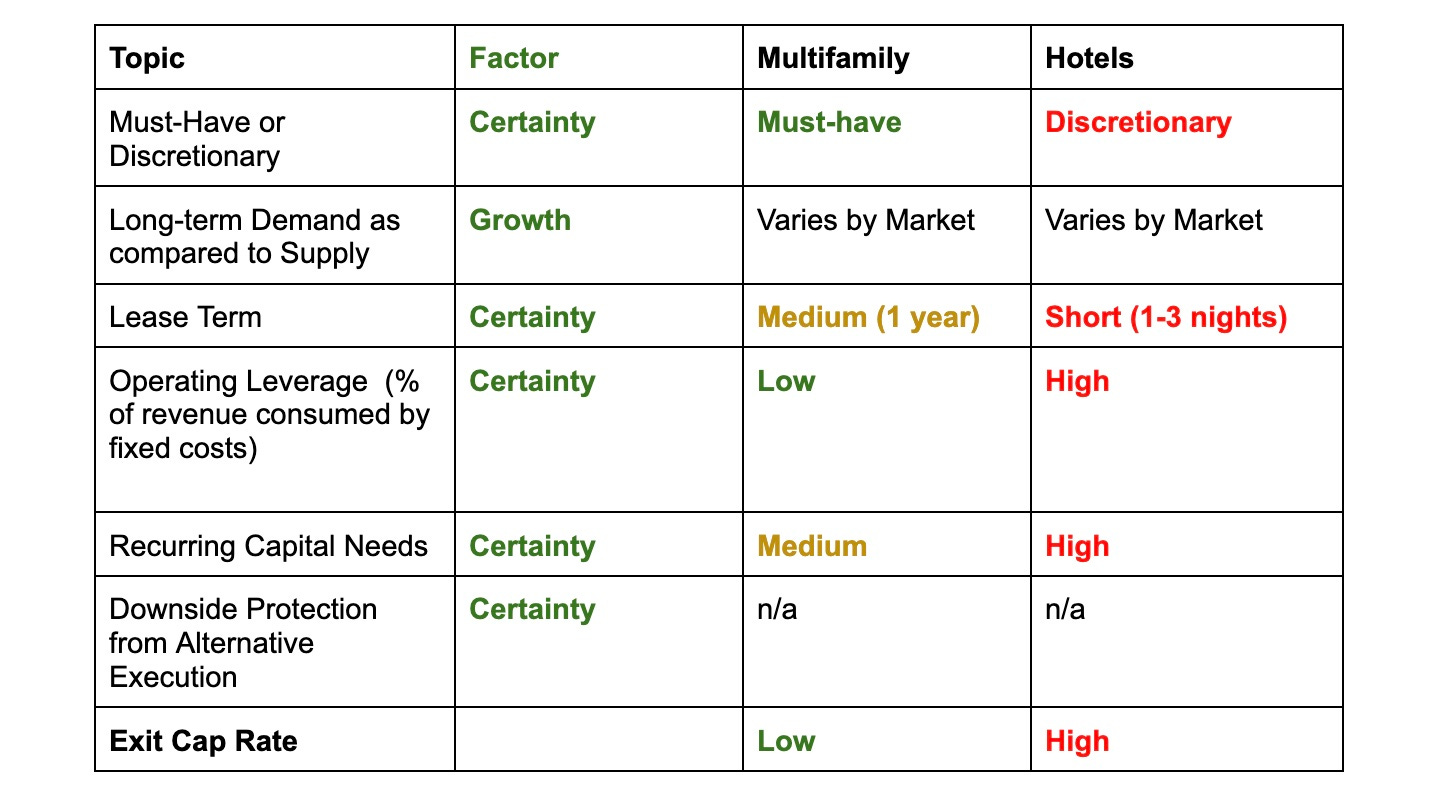

Historically, candidates have dutifully answered this question by starting with multifamily cap rates at the low end and hotel cap rates at the high end. Fundamentals informed that order: Apartments are need-to-have goods (necessity implies inelasticity in consumer demand for apartments; everyone needs somewhere to sleep!) with relatively long lease term, low operating leverage, limited capital expenditures, and cheap (sometimes government-subsidized) debt.

Conversely, hotels are more commonly seen as nice-to-have goods and have typically been both seasonal and cyclical with high fixed costs (and thus operating leverage), expensive debt, and short (near nightly) occupancy terms. In short, hotels offered riskier income with similar growth prospects to apartments; as a result, they have historically traded at a higher cap rate.

That comparison is summarized in the chart below.

If you were asked this question, you likely rooted your answer in fundamental concepts rather than public market comparable valuations or “comps” (e.g. implied cap rate of publicly traded REITs) or private market comps (e.g. implied cap rates from property sales). We knew that while in the short-run markets can be volatile and capital flows can dominate, in the long-run comps would follow the fundamentals, not the reverse.

But after years of experience working with real estate investors, I’ve found that some investors—many of whom aced that first interview question—have shied away from looking at the fundamentals when faced with how to value novel asset classes.

When considering novel assets (like flex-term rentals), investors often look to find public or private market comps for the answer rather than analyzing the underlying real estate fundamentals to arrive at an exit cap rate from first principles. Of course, at the inception of any new real estate asset class, there isn’t enough data available to come to a fundamentals-driven conclusion on what a long-term market cap rate should be.

This leaves opportunity on the table. Alpha comes from a differentiated view between how the market currently prices an emerging asset class and how the market will price that asset in the future. By using market comps as the underpinning for an exit cap rate, an investor is limiting his or her ability to have an informed (and potentially differentiated) view on the aspect of an asset’s valuation that matters most.

The rare investors like Blackstone, TPG or KKR who historically have formed an independent perspective on a nascent sector’s cap rate have improved their returns from cap rate compression as the sectors matured. Formerly niche industries like self-storage, SFR, and data centers offer proof. Green Street Advisors has measured a decline in cap rates in each of those sectors over the past decade, implying an increase in real estate value. Even after adjusting for cap rate compression due to declining interest rates, Green Street’s data show that cap rate spreads have compressed in these once niche sectors. Said another way, cap rates have declined even more than interest rates implying outsized value generation.

Self Storage: ~250bps compression (or 10bps per year)

1.80% spread to the cost of debt in 1999

(0.68)% spread in 2023

Data Center: ~300bps compression (or 23bps per year)

2.81% spread to the cost of debt in 2010

(0.21)% spread in 2023

SFR: ~130bps compression over just 5 years (or 27bps per year)

0.30% spread to the cost of debt in 2018

(1.03)% spread in 2023

In each of those periods, cap rates compressed on a relative basis more than a constant benchmark cost of debt compressed.

In each sector’s early years, investors were worried about a lack of market comps and were therefore assessing excess risk relative to what fundamental analysis of the riskiness of the cash flows, expected growth rate, and capital needs would imply. That stands in stark contrast to fundamentally oriented investors who were able to invest at a large discount relative to fundamentals–and as a result, generate alpha.

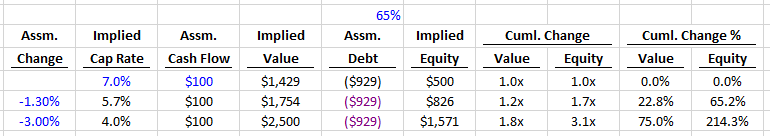

Experiencing a 130bps-300bps improvement in cap rates for an asset that has 65% LTV leverage is the equivalent of generating an extra 1.8-3.1x multiple on an investment without requiring any other change in the underlying investment. Said another way, using first principles fundamental analysis rather than comps led to 1.8-3.1x outperformance by investors deploying capital into niche sectors as they matured.

In sum, fundamental analysis for the cash flow profile of a nascent asset class matters. The alpha an investor can achieve just by engaging with an asset class’s fundamentals can outweigh just about any other operational improvement or assumption in a financial model.

With that context, let’s dive into applying fundamental analysis to furnished flex rentals.

A fundamental approach to valuing multifamily assets with flex rentals

Defining Flex Term Rentals

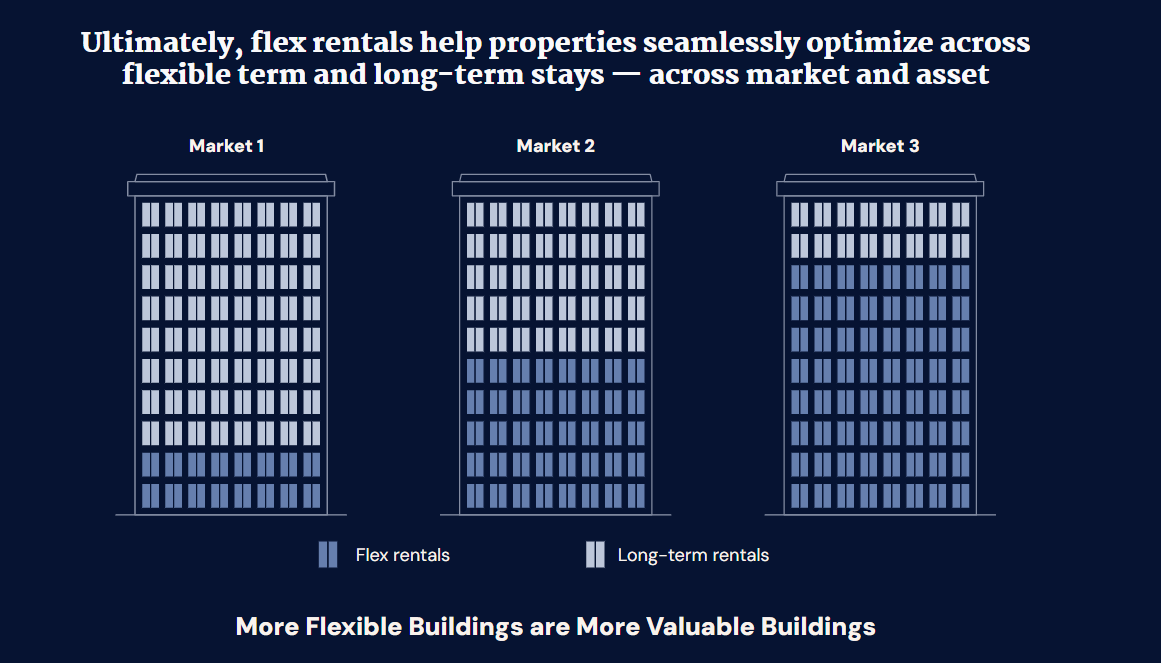

First, let’s define a flex rental or short-term rental unit in this context: a multifamily unit that is furnished and rented to guests for any length of stay, but particularly for stays of fewer than 30 days. The goal of implementing flexible furnished rentals for an owner in an apartment building is to increase the income that a multifamily property generates while decreasing risk.

A flex rental property generates more NOI because it is able to satisfy a growing need for flexible furnished housing, and serve a growing segment of consumer demand for the same. Flex-term rentals typically generate more NOI than an unfurnished 12-month rental due to higher revenue despite lower operating margins. The below table illustratively summarizes the financial impact for one unit in a given month of operation.

Further, the best flex rental programs also help lease up the remainder of the building (in Kasa’s business, 5-10% of stays are ‘try before they buy’ prospective renters). This improvement in leasing velocity for the unfurnished component of a flex rental building helps to further amplify the improvement in income generated by flex rental.

The impact of this increased income can be most impactful to a new development where the ability to implement flex rentals can help buy down basis by generating cash flow earlier, help partners reach stabilization before a perm refinancing or partnership event, or help source equity or debt financing for a project.

A property that implements furnished flex rentals can also generate less risky cash flows for two reasons: One, the asset is serving two uncorrelated demand streams, short and long-term stays. An asset that can implement STR can backfill apartment vacancy with STR units and backfill weakness in STR demand with traditional multifamily units. If one market weakens, the asset can create a floor on NOI through the other. The flex rental units can also remain furnished and be leased out for a longer term. Since the income streams are not correlated, this creates diversification of cash flows. Two, the asset is more protected from increased apartment supply; if occupancy drops, the building can dial up flex rentals to maintain NOI.

The fundamental advantage of STR execution is the ability of the Owner to create outsized cash flow during a hold period with downside protection, which creates “Asymmetric Upside”. In a base case, properties with STR produce outsized cash flows. In a downside case, they produce the same cash flow a traditional multifamily property would produce. Said another way, a buyer with STR in their toolkit produces a base case return that is higher than their competition and a downside case that is equivalent to every traditional buyer’s base case.

Valuation of Flex Rental Income

Assuming flex rentals generate increased and uncorrelated income for apartment owners, it is important to understand how to treat that income from a valuation standpoint. Rather than rooting one’s answer in comps–which are becoming more numerous but are still few–or taking the shortcut of applying a hotel-cap rate to the cash flow, a savvy investor should use a fundamental analysis grounded in the cash flow dynamics of STR.

Bottoms Up Fundamental Valuation Framework

The best fundamental analysis for STR valuation splits the cash flow that a furnished flex-term rental generates into two components: (i) The portion that would have been generated if the unit were operated as traditional unfurnished multifamily, which can be achieved with de minimis switching costs (moving furniture) or by leasing the furnished inventory as long-term rentals and (ii) the portion that represents the premium cash flow generated by operating the unit as a flex-term rental.

I suggest valuing the first portion at a multifamily cap rate and the incremental cash flow from operating the unit as a furnished flex-term rental at a higher cap rate.

As mentioned earlier, a cap rate is the function of a cash flow’s certainty (r) and its growth (g).

Let's take another look at the chart on Multifamily vs. Hotel cap rates in this context.

Let’s break these variables down as they relate to flex rental or STR properties:

Must Have or Discretionary: Demand for flex rental product has demonstrated that it is more resilient than hotel demand. During the COVID-19 pandemic (early 2020 to late 2021), Kasa’s flex rental product performed at a ~2x RevPAR penetration index (RPI) relative to hotels, a near 100% increase in RPI from prior to the pandemic. We were not alone - this was the pattern seen across the industry. This is a result of the ability to market the furnished units for longer stays. In the worst case, if hotel demand takes a dive, a furnished rental can always be rented as a long-term furnished lease. To that end, in the pandemic, our average length of stay increased by 5x to 20-30 days, up from 5-7 days. This kind of demand-side flexibility is largely impossible for hotels, and demonstrates that flex rental demand is more resilient than that of hotels. As demand from consumers for more flexible forms of housing grows, we expect flex rental to continue to shift further away from hotels and demonstrate a ‘must have’ resiliency in downturns.

Long Term Demand as Compared to Long Term Supply: There are several material, secular consumer trends creating tailwinds for demand in the alternative accommodations sector. These include a consumer preference shift to experiences (travel) over goods, the prevalence of smartphones, the emergence of the sharing economy, digital nomadism and hybrid work, and the rise of bleisure travel.

Skift and Goldman Sachs estimate that short term rentals commanded a 14% market share of global lodging demand in 2022, as compared to 10.9% in 2019 and 7.3% in 2012. JLL estimates STRs accounted for 18% of global lodging demand in 2022.

Lease Term: Naturally, the length of stay at flex rentals are materially shorter than a 12-month multifamily alternative. But it is worth noting that a typical short-term rental operator’s average length of stay in its multifamily products is 5-8 nights, which compares to a typical hotel asset’s average length of stay of 1-3 nights. This helps Kasa and other flex-stay operators generate favorable operating margins and lower risk than traditional hotels. Further, as mentioned earlier, flex rentals can be leased for much longer terms (including a year) but have the added ability of being leased more profitability for shorter periods which unfurnished rentals do not.

Hilton Worldwide, Hyatt Hotels and Marriott International all introduced extended-stay brands this year. Last year, Best Western International and Wyndham Hotels & Resorts announced new brands in the space, as did Choice in 2020. “It’s as hot as it can get,” according to Jan Freitag, national director of hospitality market analytics at CoStar.

Operating leverage: Kasa and other high performing operators typically generate gross operating margins of 60-70% at flex rental properties, which compares very favorably to hotels that typically generate 30-50% gross operating margins. That is a function of several factors but largely is a result of (i) a reduction in fixed costs at the property due to centralizing some operating systems and automating or digitizing others, (ii) a longer length of stay which reduces costs per occupied room night, and (iii) a higher RevPAR due to a superior value proposition to guests [multiple bedrooms, a kitchen, etc]. While multifamily GOP margins are typically in line or higher than any STR or hotel operation given the low touch required in the business, STR can generate a material nominal GOP premium to the multifamily alternative given higher revenue.

Recurring Capital Needs: The leading flex rental operators have robust trust & safety systems (including decibel meters and marijuana sensors) which reduce incidents that can have a negative CapEx impact by >90% relative to industry average.

It is worth noting that the STR use requires incremental capital relative to a multifamily use through the acquisition of furniture, which should be viewed as an ROI driving project (like appliance upgrade or back-splash upgrade, but with better payback). However given this is a study of exit value we can assume furniture has already been acquired.

Adding furnished flex rentals to the chart illustrate some of the short-term rental industry’s advantages over traditional lodging. Our view is that flex rental cash flow should not trade at a lower cap rate than multifamily cash flows, but it should trade at a lower cap rate than hotels.

In fairness, there are factors outside of the grid above that add some degree of added uncertainty to flex-stay rentals. The first is legislative risk. Some units rented as flex rentals can be at risk of legislative ban. However this risk usually comes after a very lengthy public and private review process, can occur only in multifamily buildings where the units are not permitted under hotel licensing, and is largely focused in markets where there are not mature, established regulations on the books already (a diminishing number). Operating a property that is licenseable both as a hotel and as multifamily mitigates this risk fully. Most leading flex rental operators including Kasa can help you ably navigate this risk.

Another potential risk is that trust and safety measures may disrupt the traditional rental business. This fear overstates the operational risk from using the best operators in the flex rental space, all of which have robust trust and safety response measures and teams. To use Kasa statistics: our company has T&S related incidents at fewer than 0.02% of its stays, around 90% better than non-professionally hosted Airbnb stays.

Finally, lenders may not give any value to the incremental revenue from a flex rental use and require borrowers to limit flex rental use or ask for premium pricing. We have seen first hand that with the right lender playbook and education, lenders come to realize how a flex rental use improves the value of their collateral, and as a result give appropriate credit to that use. This is another area where a leading flex stay operator can help provide data and a playbook to complement an investor’s strong relationship with lenders to lead to the strongest possible execution.

In all cases, these risks are all mitigated by the ability of an owner to convert back to a traditional multifamily use or simply rent the furnished inventory longer term when it is required or opportunistic to do so.

Recommended Valuation Methodology

Our recommended valuation framework takes into account the fact that a multifamily footprint which is being operated on an STR basis can always be converted back to a traditional multifamily use.

As such, I suggest splitting the cash flows from an STR unit or building into two, untrended, stabilized cash flows:

The multifamily rent equivalent cash flow (or “MF Cash Flow”) represents the cash flow that the unit would have produced if operated as traditional multifamily product on a traditional 12-month unfurnished basis

The short-term rental cash flow (or “STR Cash Flow”) represents the cash flow that the STR unit produces operating as a furnished flex-stay rental.

The difference between (2) and (1) is called the “Incremental STR Cash Flow”.

To value the cash flows, I recommend the following:

A multifamily cap rate should be applied to the MF Cash Flow to produce a “MF Floor Value”

A STR cap rate (more akin to a hotel cap rate but slightly lower due to lower operating leverage, greater lease term, lower capital needs, and stronger long-term demand relative to supply fundamentals) should be applied to the Incremental STR Cash Flow to produce “Incremental STR Value” We believe this to be a 50-150bps spread to the multifamily cap rate.

Total valuation should equal the Multifamily Floor Value plus the Incremental STR Value

Illustrative Case Study

Let’s look at a case study under the following assumptions:

Consider a multifamily asset with 300 units and $2,000 per unit per month market rents.

Assuming 3% other income, 5% general vacancy, 0.5% bad debt, the asset would produce around $7m of net multifamily rental equivalent, or $1,947 per unit per month

At a 70% NOI margin, the implied NOI is $4.9m or $1,364 per unit per month

Lets now assume that a STR operator takes over 30% of the units and can remit to owner a 40% premium to the net multifamily rental equivalent

Note: assuming a 65% net operating profit margin, well within Kasa’s existing performance, would imply the operator would need to generate a $138 RevPAR, reasonable based on performance to date in a typical market and property

Holding Multifamily Gross Operating Expenses constant (conservative, given the owner’s lower turnover costs), the asset would generate $5.7m NOI on a pro forma basis, implying incremental STR NOI of $0.8m

Cap rates will obviously vary depending on market, asset quality and risk-free rate. But by illustratively applying a 5.5% cap rate to the multifamily income ($89.3m or $298k/unit value) and a 7.0% cap rate to STR income ($11.7m value), the implied exit value is $101.0m or $337k/unit and the blended cap rate is 5.7%

STR use produces an incremental $11.7m or $39k/unit or a 13% increase in multifamily only value by only operating 30% of the inventory. On a 65% leveraged asset, this is the equivalent of adding almost a half turn to the multiple.

Despite the fact that the exit cap rate is wider than a multifamily-only execution, STR use remains accretive given the outsized cash flow generation

A sensitivity analysis below shows the implied value creation from STR use under varying building mixes and premiums to multifamily rents (but the same cap rate and other assumptions as above). You will note that there is zero value diminution even if STRs produce a negative cash flow relative to MF rents - that is because a STR operator can be terminated at sale and the units can be converted back to multifamily for near de minimis costs (move out of furniture and arguably some lease-up carry costs, which can be limited via phased move outs).

A brief note on capital flows

Fundamental valuation frameworks are all well and good until human nature and supply & demand of capital get involved. As such valuation can also be impacted by flows of funds. If there is a large increase in capital chasing a limited supply of an asset type, pricing for the asset class should generally go up and cap rates should decline. In theory [and this has also consistently proven out in practice], over longer time horizons, the capital flows (both debt and equity) should follow fundamentals, such that asset classes with less risk and higher growth prospects should attract more capital by virtue of the capital invested in those assets delivering superior returns. In the short-run, however, the two can diverge.

Broadly, it increasingly seems as if capital formation favors flex rentals. At an intuitive level, a property that can be operated as both a hotel and an apartment can have a wider buyer pool as both prospective hotel buyers and multifamily buyers may be interested in it. Hotel properties on the other hand don’t attract apartment buyers and apartment properties don’t attract hotel buyers.

Further, over the last several years there has been early but meaningful capital interest in flex furnished rental strategies. More recently, multiple dedicated strategies have been created by high-profile investor groups targeting the sector. These strategies run the gamut (from ground-up development of furnished rental housing (i.e. “build to stay”) to acquisitions of stabilized apart-hotels). These serve as leading indicators to what we expect will be a large-scale flow of capital into a maturing sector, resulting in material cap rate compression over a reasonable hold period.

Further, while capital demand for properties that can support furnished flex rentals is increasing, the supply of buildings that can support flex rentals is limited. Only certain properties with specific underlying zoning can support furnished flex rentals. In any given market, only a subset of multifamily properties will have the right zoning characteristics (typically, zoned for hotel) to support flex rentals. As a result, an increase in capital flow demand will eventually find a more limited supply for such properties, which should lead to higher prices and lower cap rates over time.

Debt: In theory, a lender should be more excited about a property that can access both flexible furnished demand and unfurnished demand (versus one that cannot). The former building represents stronger collateral that can be taken back, sold, or converted to a different use in times of trouble. Downside protection from the ability to switch back to unfurnished multifamily or to simply lease the furnished inventory long-term & the diversification benefit from an uncorrelated demand stream reduces the risk profile of cash flows for assets with STR versus ones without it. In practice, lenders can move slowly and it takes some education to ensure lenders understand this dynamic. Equity groups that are able to educate lenders will have an edge over those who are not.

Comps: Given the STR sector’s nascency, there are limited sale comps to show investors a clear-cut case of how exit cap rate valuation has worked in practice. Kasa has been either an operator or a prospective operator listed in the OM on 7 trades for which Kasa represented 5-20% of the unit mix in the last 18 months. These assets have traded in-line with multifamily comps but the data is too early to be conclusive.

As the flex rental space matures and the multifamily market thaws, it will be interesting to track how buyers engage with flex rental product. Savvy investors who deeply understand the fundamentals will be well positioned to create alpha.

—Roman Pedan

Thank you to Brian Ritter for his help on this letter.