Nine Reforms That Could Dramatically Accelerate Housing Production

While challenges to single-family zoning draw attention, other reforms could have an even bigger impact. Real estate investors should be paying attention.

Thesis Driven dives deep into emerging themes and real estate operating models. This week’s letter explores practical policy reforms that could rapidly accelerate housing production in the US and beyond.

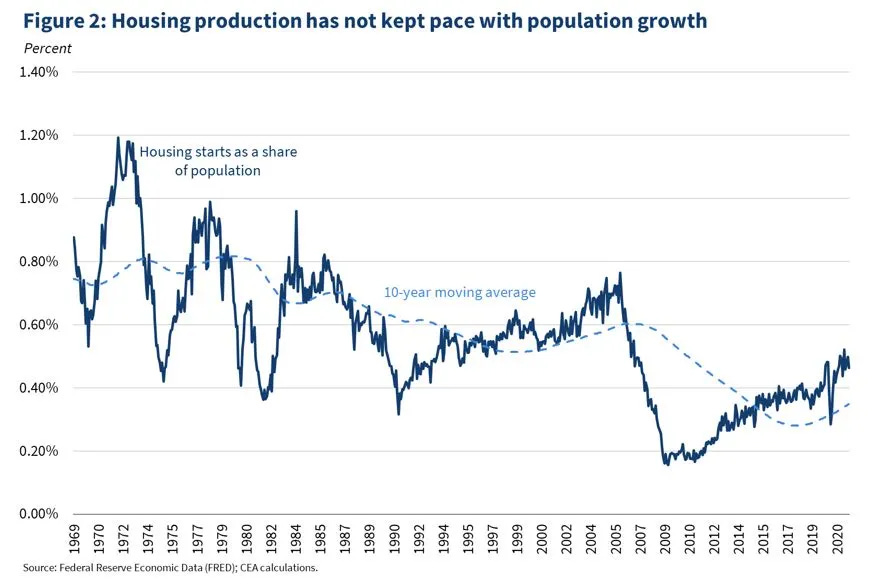

A simple reality has been gaining steam in state legislatures and city councils across the US: we have to build more housing. Decades of sluggish urban housing development has led to economic stagnation, a homelessness crisis, and an increasingly rent-burdened middle class. Over the past few years, legislative efforts have begun to roll back land use restrictions in ways previously unthinkable, including the end of single-family zoning in a number of states and cities. Politicians from New York Governor Kathy Hochul to Montana Republicans to west coast leftists are pushing increasingly notable reforms.

But housing advocates are learning that there are no silver bullets to bring us housing abundance and affordability. The regulatory apparatus that makes building housing costly and onerous has been accumulating for decades. Restrictive rules and mandates can be found everywhere—state and local—and are often overlapping, requiring a coordinated approach between various levels of government to unlock housing development.

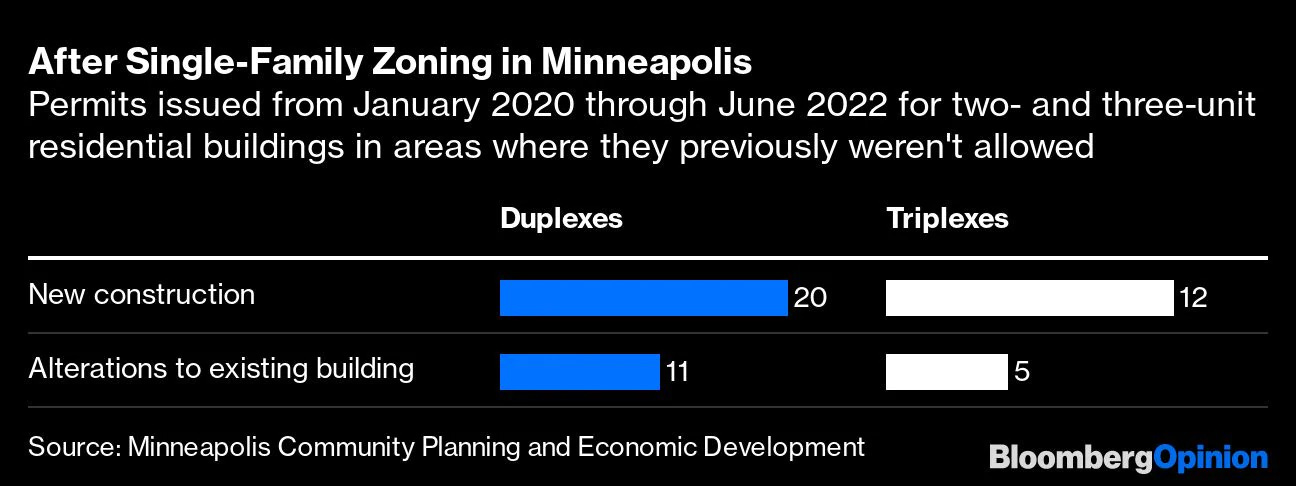

The silver-bullet mindset inevitably yields disappointment when a single reform doesn’t rapidly accelerate housing production. The recent push to end single-family zoning is a clear example. While noble and the right thing to do, legalizing fourplexes alone is unlikely to usher in a wave of missing-middle housing development. Other rules—minimum lot sizes, FAR and building envelope restrictions, and owner-occupancy requirements, to name a few—blunt the impact of zoning reform on its own. Minneapolis’s seemingly bold move to end single-family zoning in 2018 offers a cautionary example, as the number of new units actually unlocked by the change is measured in dozens rather than hundreds or thousands.

Making housing development easier isn’t just about fixing zoning. Building codes as well as occupancy laws have an impact, as do non-regulatory changes such as ensuring that local building departments are sufficiently staffed to speedily process permit applications. Building code and staffing reforms are less high-profile than sweeping zoning changes but are just as critical to housing development.

Challenges aside, the ideas that (a) housing production must increase and (b) land use regulations are a barrier to housing production are gaining political steam. Real estate investors would be wise to pay close attention to these changes—both as a potential competitive threat to existing portfolios as well as an opportunity to build new multifamily housing in areas previously off-limits.

As housing advocates’ focus moves past big-headline zoning changes into the sticks-and-bricks details of enabling housing production, here are nine meaningful reforms we may see on the agenda:

Legalizing ADUs Without Strings Attached

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) – also known as in-law units or granny flats – are small homes often added to the backyards of existing single-family residences. Given their relatively small size–new ADUs in California average 615 square feet–and lack of a dedicated yard, ADUs are often much more affordable than traditional single-family homes.

Small and often invisible from the street, ADUs can be an easy housing reform for many local elected officials to support. Unfortunately, many ADU legalization programs include strings that make them unlikely to become a meaningful source of attainable housing. Often, local ADU programs include owner-occupancy requirements, preventing investors from densifying single-family neighborhoods through ADUs at a scale required to impact housing supply. California eliminated its ADU owner-occupancy requirements in 2020, which led to a number of startups, operators, and investors taking interest in the sector and bringing new housing to market.

However, other jurisdictions have embraced poison-pill ADU regulation, such as Los Angeles’ interpretation that building an ADU puts the primary residence on a lot under rent control if it was built prior to 1978. While elected officials may be hesitant to make single-family neighborhoods more appealing to investors, bringing ADUs to market at the kind of scale needed to impact housing affordability is unlikely to be accomplished by an army of single-family homeowners investing their personal savings. Any serious attempt to use ADUs to address housing affordability goals must be able to tap the capital markets.

Minimizing Parking Minimums

In many urban areas, the cost of building an underground parking garage can top $100,000 per parking space, adding more than 20% to the total cost of building a new residential unit. In most cases, developers can’t recover these costs in monthly parking fees, making excess parking a very expensive–and often legally-mandated–amenity.

Given that the cost of building excess parking must be baked into a project’s financials–and passed through in the form of higher rents–parking minimums effectively act as a subsidy to car owners borne by car-free renters. Despite their ostensible climate goals, many dense American cities including New York still have strict parking minimums on new developments, even those near transit, forcing developers to reinforce their communities’ car dependence by building more parking.

There is also little evidence that developers will chronically build less parking than is needed by tenants unless mandated by law. Specifically, construction lenders often view parking-light projects skeptically, and building additional parking can make residential projects easier to finance. In many cases, developers themselves choose to build more parking than is required by law, possibly inspired by COVID-era trends of increased urban car ownership. Despite these trends, there are a number of places in the US where car ownership is sufficiently optional–and parking construction is expensive enough–to make a positive impact on housing affordability.

Curtailing Impact Fees

The simplest way to make multifamily housing more feasible is to simply stop charging developers additional fees to build it. Increasingly, cities are charging per-unit “impact fees” to developers who wish to build multifamily housing. In some jurisdictions–particularly in California–those fees can top $50,000 per unit, raising total development costs by up to 10%.

While cities starved of tax revenue by Proposition 13 inevitably need to find new sources of cash to fund city services, placing a Pigouvian tax on new housing construction in the middle of a housing crisis may not be the best place to look. While in a best-case scenario these fees should fall on landowners in the form of lower land prices, land has many uses, and yesterday’s multifamily development site may be tomorrow’s self-storage project.

Legalizing SROs

In the early 20th century, millions of Americans lived in residential hotels: flexible urban apartments typically rented weekly, often with shared dining facilities. Americans of all socioeconomic classes lived in residential hotels, and they ranged from luxurious to spartan. They were an essential component of urban workforce housing; in 1910 San Francisco, over 15% of the city’s population lived in residential hotels compared to 2.2% today.

But midcentury white flight and urban decay led to the terminal decline of the residential hotel. Now associated with crime and blight, many cities began demolishing their residential hotel stock, re-branding the hotels as “single room occupancy” (SRO) dwellings and banning their development. With the City’s encouragement, developers destroyed or repurposed over 100,000 SRO units in New York during the 1970s and 80s alone.

Today, SROs in many cities—including New York and San Francisco—sit in an odd regulatory paradox. While it is still largely illegal to build new SROs, the destruction of existing SRO units is also extremely difficult, an acknowledgement of their crucial role as housing of last resort. In a regulatory environment where things are increasingly either mandated or prohibited, SROs happen to be both at the same time.

Given the homelessness crisis gripping many major US cities—and the success of micro-apartments in Seattle, where they have been adopted at scale and as small as 150 square feet—broadly legalizing the creation of new residential hotels would enable to market to provide housing to many lower- and lower-middle income people that currently rely on government subsidy. A robust residential hotel stock would also make those government subsidies go much further, with each housing dollar putting a roof over more heads. Houston has done a better job addressing its homelessness crisis than many coastal cities not because it is more generous, but because each housing dollar goes further in a city with more abundant (and cheaper) housing.

Legalizing point-access block apartments

In the United States, most building codes require any structure taller than four stories to have two separate staircases. This forces the “double-loaded corridor” design—with apartments on both sides of a hallway—common in American apartment buildings. There are some serious drawbacks to this design: most apartment units will only receive natural light from one side, and the double-stair requirement makes many smaller sites infeasible for multifamily development. Legalizing single-stair buildings would allow the construction of point access block apartments, common in Europe and much more efficient than double-loaded corridor structures, particularly for small sites.

While fire safety is the primary concern with single-stair buildings, the US has a worse fire death rate than most European countries where single-stair buildings are the norm. In addition, the majority of US fire deaths are in 1- and 2-family homes, many in older, wood-frame structures lacking modern electrical wiring and HVAC. Replacing these structures with modern point access block apartments would likely reduce the overall fire death rate.

Ending Minimum Lot Size, Envelope, and Setback Requirements

Minimum lot sizes, setbacks, building envelopes, height maxima, and other requirements create a web of complexity and regulation that greatly limit the effectiveness of “silver bullet” solutions such as the abolition of single-family zoning. While a city council or state legislature may make it legal to convert a single-family home to a fourplex, the conversion is unlikely to make financial sense if setback and building envelope restrictions don’t allow additional square footage to be built. And even if it does make financial sense, the resulting units will likely be small and compromised, effectively replacing family-friendly housing with cramped apartments.

In addition to making housing development difficult, these regulations make our cities worse places to live and are directly at odds with the kind of walkable, “human scale” density that many Americans say they want. The kind of early 20th century urbanism found in the center of many small American towns—2-to-4 stories of height with ground floor retail, high lot coverage, and no setbacks—would be explicitly illegal to build almost anywhere today.

Legalizing Lot Subdivisions

The legalization of lot subdivisions is an important corollary to eliminating minimum lot sizes, as it enables the densification of existing single-family neighborhoods through lot splits. In 2021, Caifornia passed SB9, which legalizes the subdivision of any single-family lot. In combination with California’s aggressive ADU legalization discussed earlier, SB9 effectively allows any single-family lot to be converted to four units through a lot split combined by ADUs on each new parcel.

Unfortunately, SB9 had an insignificant impact on permit activity in its first year. Experts at the Terner Center cite other regulatory hurdles identified here–owner-occupancy requirements, high impact fees, and building envelope restrictions, to name a few–making SB9 lot splits unappealing to most homeowners. Once again, regulatory changes cannot happen in a vacuum; there are no silver bullets to housing abundance.

Allowing Demolitions to Retain Grandfathered FAR

There are a number of zoning and building code barriers preventing easy conversion of vacant office buildings to residential apartments. While Thesis Driven covered some of those barriers - and the developers pushing through them - in a prior letter, it would often be cheaper and more effective for developers to demolish aging office assets and rebuild from scratch.

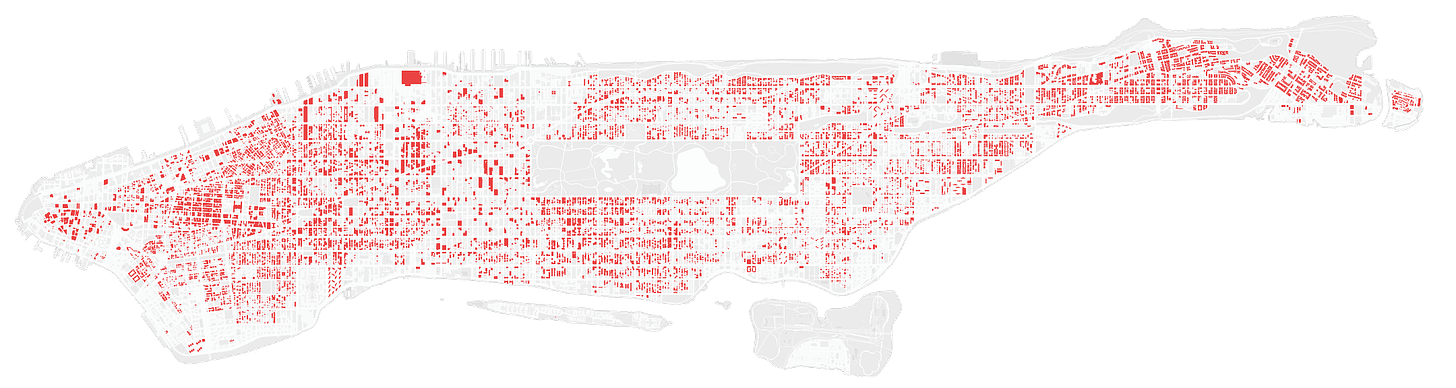

However, demolishing an existing structure creates a major problem in many cities: the site loses any grandfathered FAR and the rebuilt structure must be smaller than the original. This is a particular problem for office buildings built prior to the downzonings that happened in many American cities in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. After all, 40% of the buildings in Manhattan couldn’t be built today under current zoning.

Of course, abolishing FAR entirely would be a much more powerful solution—and a bit of a cheat code for housing affordability—but is unlikely to be politically feasible in many places.

Fully Staffing Local Planning, Building, and Utility Departments

In real estate, time is money. Each month that a project is stalled waiting for plan approvals – or worse, sits vacant waiting for utility hook-ups or a certificate of occupancy – raises the cost as the developer sits on an expensive construction loan, unable to build, stabilize, and refinance. Each month that goes by with an apartment project unbuilt or unopened is also a month that its future residents can’t live there.

In almost all cases, these delays are due to city agencies being insufficiently staffed, often because their salaries for key technical positions—such as plan examiners and utility technicians—haven’t kept up with the market. But I have yet to meet a developer that would be unwilling to pay a bit more in filing fees to ensure that their plans are examined quickly and efficiently. After all, the relatively minor filing fees pale in comparison to the tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt service and lost revenue that each month of delay brings to a project.

Solving the housing crisis doesn’t have to be difficult. We have the capabilities and capital to achieve Houston- (or Tokyo-) level rents in every major city in the developed world. This alone won’t address the housing needs of the lowest-income renters, but it will make those needs far easier to meet through government interventions like Section 8 and Project Roomkey.

Five years ago, proposals like these were the sole domain of housing policy wonks. Today, housing abundance is increasingly on the agenda in state capitals and city halls nationwide, and real estate investors should keep a close eye on changing political winds.

— Brad Hargreaves

Brad that’s seriously sensible stuff. If the debate is anything like it is here, your logic will be trumped by hysteria but I really applaud your efforts nonetheless.

Great points! Suggested addition: allowing developers of for sale units to use pre sale deposits for development needs. This radically reduces equity capital needed to get started and also enables banks to offer loans at much higher LTC. Each state has slightly different rules. Florida’s is best in class in my opinion:

http://www.leg.state.fl.us/statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&URL=0700-0799/0718/Sections/0718.202.html