Everyone wants more affordable housing.

The rent is too damn high, particularly in America’s largest and most dynamic cities. The cost of housing locks millions out of economic opportunity, puts homeownership out of reach, and makes a meaningful dent in our country’s economic growth. New York City’s average rent is now almost $4,000 per month, pricing out families, workers, seniors, and just about everyone else.

So it’s no surprise that voters—and the officials they elect—would make housing affordability a priority. Bringing down the price of housing would be the single most significant lever to reduce the overall cost of living. Housing affordability is a winning issue.

Unfortunately—and even with the most well-intentioned elected officials—promises to bring down the cost of housing often end in a sleight of hand.

“Housing affordability” becomes “affordable housing.”

“Make housing more affordable” becomes “build more affordable housing.”

And while that sounds good, it’s a problem. Because “affordable housing” can mean many things, and what the government means when it says “affordable housing” is not what most voters mean when they demand that housing be more affordable. Voters want housing that’s abundant, high-quality, and affordable (as in inexpensive). But to an elected official or housing bureaucrat, “affordable housing” means housing that’s built under specific government programs, income-restricted, and—in one way or another—subsidized.

In other words, there’s a substantial disconnect between affordable housing and Affordable Housing.

This lexical confusion is at the root of a lot of housing policy dysfunction. “We should only build affordable housing” is a much more appealing message than “we should only build income-restricted housing” or “we should only build subsidized housing.” But from a practical housing policy perspective they all mean the same thing. And they’re all bad and perpetuate the housing crisis. But only the first message gets meaningful traction in influential progressive circles and is used to kneecap policies that would get more housing built by justifying opposition to market-rate development.

The appropriation of “affordable housing” as a term is a fairly new phenomenon. And just as housing bureaucrats shifted the vocabulary starting around 25 years ago, it can be shifted once again. Fixing our urban housing woes will require the reclaiming of “affordable housing,” separating it from subsidized housing programs:

Affordable housing is any housing that is inexpensive relative to area median income. Perhaps taking up no more than 30% of the income of a family making 60% of AMI. It could be subsidized or market-rate.

Subsidized housing is housing that is intentionally kept below market rate as part of a government initiative, be it a federal program like LIHTC (where the housing is subsidized by the taxpayer) or local inclusionary zoning mandates (where the housing is subsidized by market-rate renters in the building).

These terms would bring the language of housing policy wonks and elected officials in line with reality as well as voters’ understanding.

A bit of history

The move to “affordable housing” as a term began in the late 1990s with good intentions. Previously, affordable housing built or operated with subsidies was called “low income” housing. This term still remains in some formal language (e.g., the “LI” in “LIHTC”) but has otherwise largely fallen by the wayside.

That alone isn’t a bad thing; “low income” is both stigmatizing and incorrect. Many subsidized housing policies, after all, create units serving middle-income renters and those with incomes well above AMI. As 90s-era HUD leaders and mayors sought to encourage more mixed-income development and fewer concentrations of poverty, “affordable housing” quickly replaced “low income housing” as the term of choice.

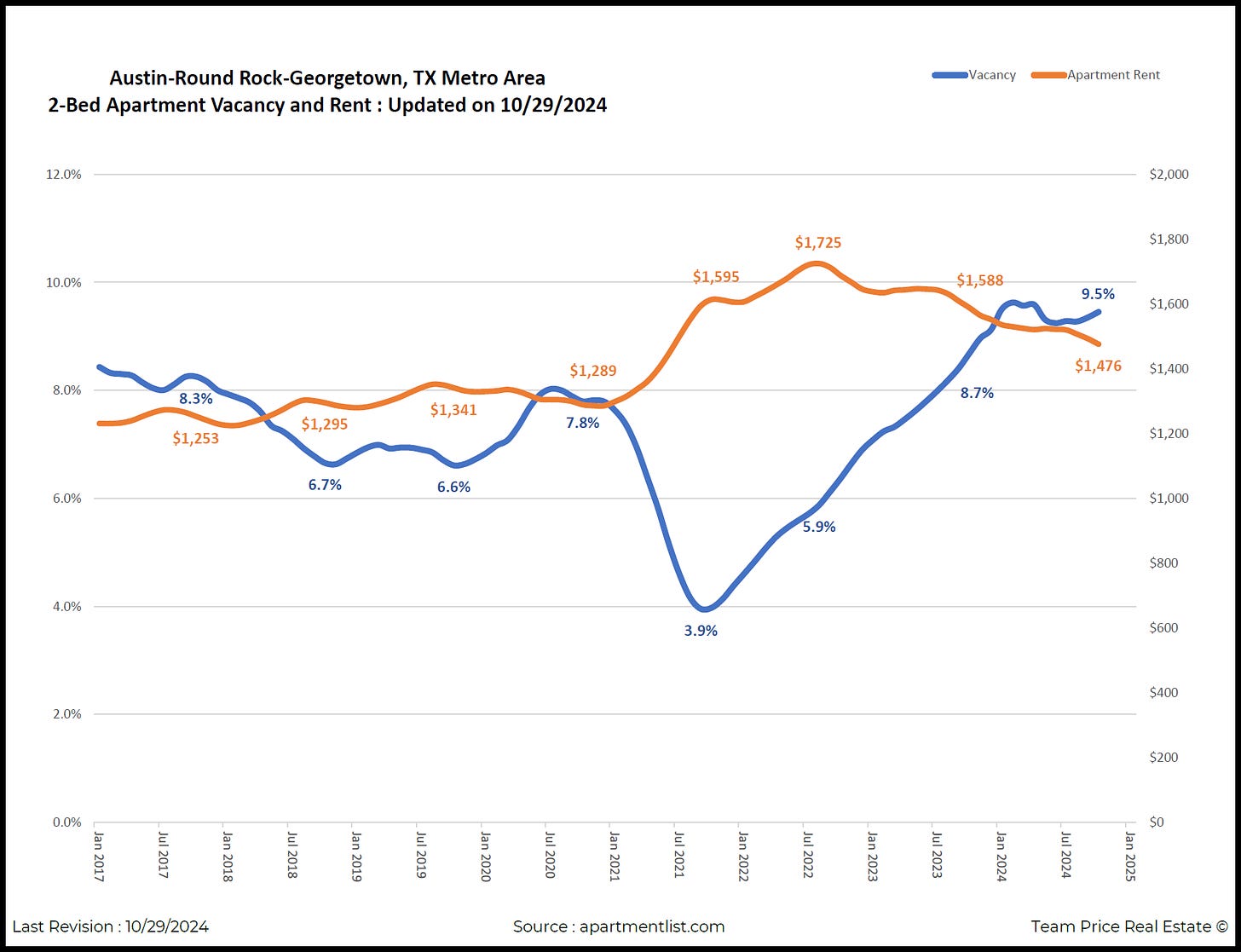

But cities are fighting a very different battle today than they were in the late 90s when America’s urban renaissance was in its infancy and cities still had underutilized structures and zoned capacity. Today, there’s plenty of capital looking to build housing in the places where people want to live. And there’s example after example and study after study that allowing developers to deploy capital and build housing brings down rents, even to the point that housing developers themselves suffer—just look at Austin, Texas today. After record apartment deliveries in 2023 and 2024, Austin vacancy skyrocketed to 9.5%, forcing multifamily owners to cut rents significantly to attract tenants. Despite being one of the hottest post-pandemic cities, Austin rents have retreated more than 50% from their 2021-22 run-up.

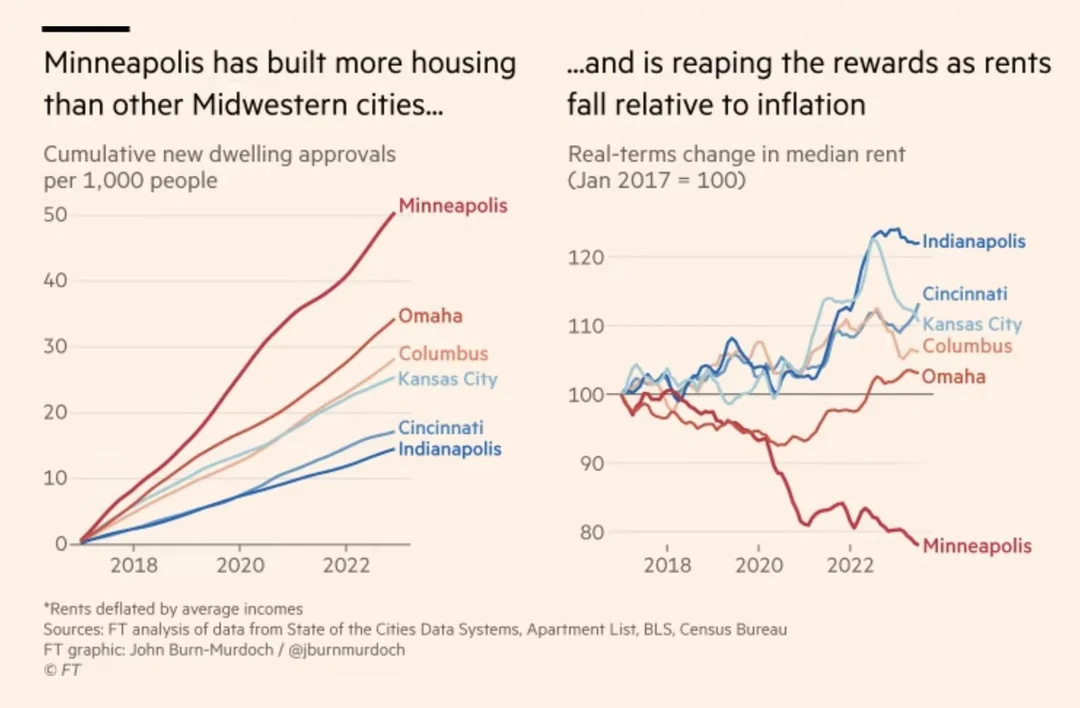

Invariably, the cities with the lowest market rents are the places that allow housing to get built. And inversely, the places with the worst housing affordability crises are those with strict growth controls.

At this point, it’s not really a matter of factual debate that more housing supply lowers rents. But that doesn’t mean midcentury growth controls are easy to roll back, as housing opponents—some misinformed and others operating in bad faith—are numerous and vocal. See the struggle that NYC recently endured to pass a very light-touch, watered down housing bill that aims to create only 80,000 net new housing units over the next 15 years—a fraction of the need.

Unfortunately, the well-intentioned choices of past decades are empowering bad faith opponents today.

In zoning- and building code-constrained markets like New York, Boston, and San Francisco, the limited market-rate housing that gets built is going to be expensive. When you limit the supply of something, the price goes up. So the market-rate units that do get delivered in these cities tend to have eye-watering rents.

Obviously people find this frustrating, empowering elected officials to demand that developers focus on building affordable housing—and perhaps affordable housing alone. “We don’t need more housing, we need affordable housing” is a common refrain from left-leaning politicians from New York to Toronto to San Francisco. Of course, they don’t mean “affordable housing” in the vernacular sense of “low rent”; they mean subsidized housing built through any number of government programs.

Policymakers have a number of tools at their disposal to ensure that only subsidized housing gets built. New York, for instance, has punitive base property tax rates for any building larger than 6 units. These taxes, however, can be abated by putting rent and income restrictions on a number of the newly-constructed units. Other municipalities create onerous planning and approval processes, only exempting housing that’s rent- and income-restricted such as Los Angeles’s ED1. But by far, the most pernicious “affordable housing” policy is inclusionary zoning.

Understanding Inclusionary Zoning

In brief, inclusionary zoning refers to a set of policies that intend to create more income- and rent-restricted units by mandating that housing developers rent a certain percentage of newly-constructed units for below market rates.

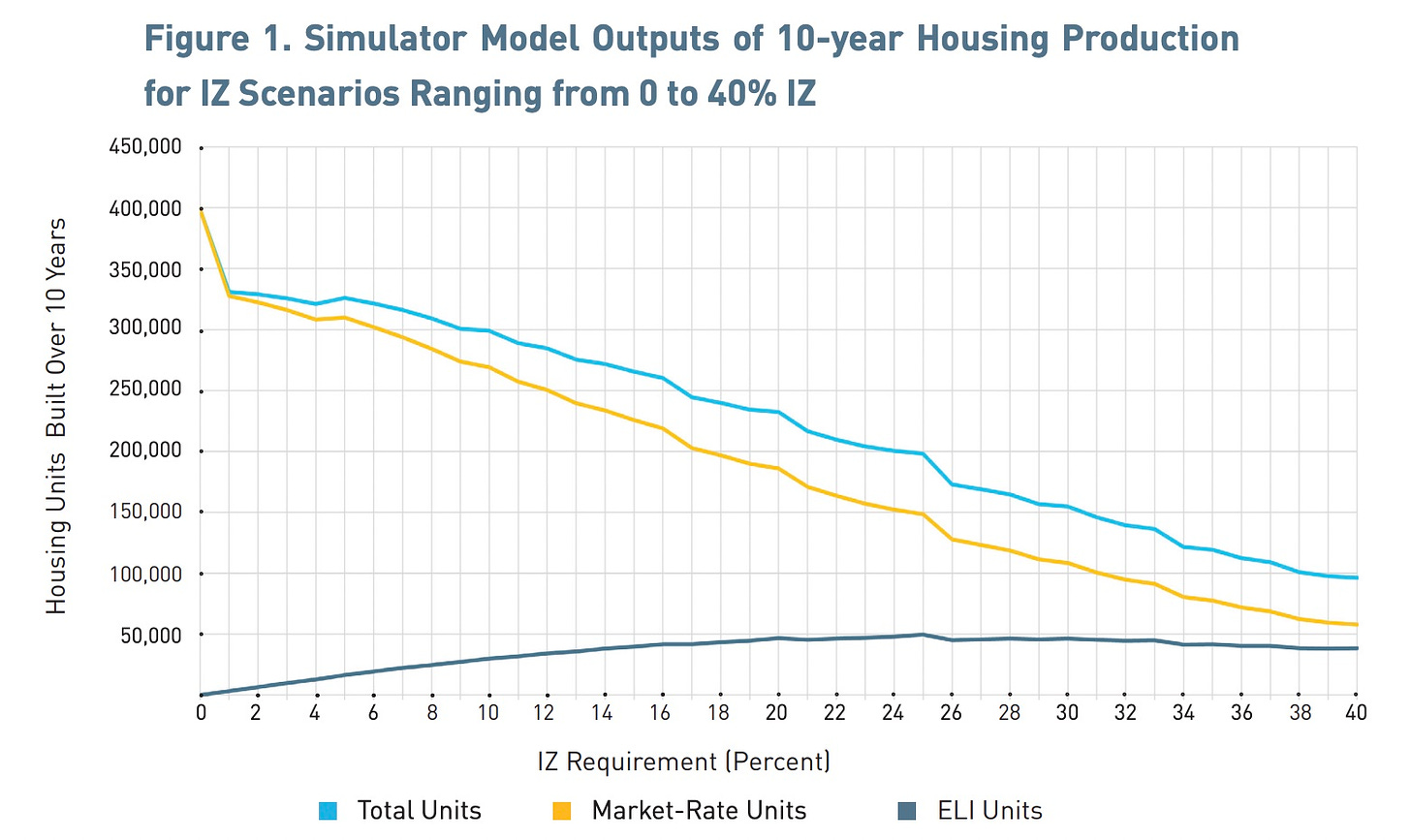

These policies inevitably depress the amount of housing that actually gets built. A 2024 Terner Center study of Los Angeles’s IZ program showed that even small IZ requirements can dramatically decrease the number of units built. Going from a 16% to 25% IZ requirement, for instance, eliminated five market-rate homes for every one subsidized home added.

This relationship validates our use of the word subsidized for these units even if they don’t fall under a formal subsidy program like LIHTC. A unit that is kept below market rate is subsidized by someone—either by the taxpayer outright or by other market-rate tenants.

Analyzing a multifamily development from a financial perspective makes this painfully clear. To make financial sense in today’s rate environment, a real estate project needs to generate at least a 7% yield-on-cost. That is, if $100 million were spent creating the building—including both land and construction—it would need to generate at least $7 million per year in net income to make financial sense. For a 200 unit apartment building with a 30% opex ratio, that’s an average rent of about $4,200 per month.

But if 25% of units are required to be kept at below-market rates—say, $1,500 per month—the rest of the units at the building would need to rise by about $450 per month (to $4,650) to make up for the difference.

The developer or its investors do not “take this on the chin,” economically speaking. The yield that the project needs to generate is more or less fixed. If a given multifamily project can’t hit a 7% yield-on-cost, capital will go fund something with a better risk/reward balance: treasuries, industrial deals, corporate debt, or single-family sprawl projects in suburban Phoenix. The urban multifamily site subject to a 25% IZ requirement will sit unbuilt until market rents rise enough to reach the $4,650 number—effectively creating a circuitous subsidy from market-rate renters to below-market renters.

On Subsidies

To be clear, this is not an argument against subsidies or subsidized housing. Barring a dramatic decrease in construction costs, providing very low-income individuals and families with housing will require subsidies. Those subsidies can take the form of vouchers (as in Section 8), tax credits (as in LIHTC), direct public investment (as in public housing), or inclusionary programs where market-rate renters cross-subsidize income-restricted units.

Each of these approaches have advantages and drawbacks. But they all involve subsidies, and there’s no good-faith argument to hide that fact from voters. If we want some people to have rents below market rate—and there are good arguments to do so—someone will have to bear the cost.

From a progressive standpoint, inclusionary zoning appears to be the worst of all worlds. By putting the burden of subsidizing below-market units on renters specifically—rather than the tax base as a whole—IZ effectively acts as a regressive tax. And as the Terner Center study cited earlier showed, IZ programs maximize market distortion by discouraging housing development, artificially inflating market-rate rents beyond where they’d be without IZ. Strict IZ programs like New York Mandatory Inclusionary Zoning effectively make it impossible for cities to ever escape their housing crises; if market rates began dropping due to increased supply, projects would simply stop making financial sense until rents rose yet again.

In other words, IZ programs don’t solve housing crises; they complement them.

Voucher programs like Section 8 are far less distortional. And they’re much more effective in places that build a lot of housing where each Section 8 voucher dollar can go much further. Programs like LIHTC have also been very successful—more than 3.65 million housing units have been built under the LIHTC program since its inception in 1986. And unlike IZ, both these programs can and do exist alongside a robust market-rate rental market.

Studying less supply-constrained markets like Chicago and Houston make the “affordable housing” sleight-of-hand even more absurd. In those markets—and many others—market-rate housing is broadly affordable to residents. Houston’s median rent of $1,193, for instance, is easily attainable for someone making the local median household income of $60,440. And the city’s abundant housing has made it far easier for Houston to house its homeless population. The use of “affordable housing” to solely refer to subsidized housing is nonsensical in a broadly affordable market like Houston and only serves to obfuscate the policies that Houston used to achieve its success.

Subsidies aren’t a bad thing. They’re necessary, particularly for cities that in the throes of the toughest housing crises. But not all subsidies are the same. And there’s no reason to mislead voters on what they’re getting when politicians push policies to “only build affordable housing.” Below market rate housing is subsidized housing, and someone—often a renter—is footing the bill.

—Brad Hargreaves

Awesome article.

I look forward to walking the walk with our Pathways Community product in 2025!

#TotalTenancy

The voice of reason. Excellent article. Yes, the challenge is to make more affordable housing without subsidies. Free up the market to adapt. This is one of the most rule bound area of human activity. What would it take to permit an owner build? Can land be provided on which to locate a home on a rental rather than a purchase basis? Is it permissible to build a two bedroom, one bathroom residence as a starter home? Is it possible for owners of rural land to construct ancillary dwellings for rental?