Last week, the Trump administration announced a new task force led by the heads of HUD and the Department of the Interior.

The goal?

Unlock the development potential of the 600+ million acres of federal land to solve the housing crisis.

Most people associate “federal land” with vast expanses of Western scrubland far from any civilization—perhaps appropriate for a grazing lease but otherwise unfit for human habitation. And that association is generally true; over 90% of federal land is in the Western US, where the federal government owns significant portions of Nevada (85%), Utah (65%), Idaho (62%), and Alaska (61%), among others. The vast majority of that land is very, very rural.

But even in places the federal government doesn’t dominate, Uncle Sam is still a massive landowner. The federal government, for instance, owns more than 10,000 acres in New York City alone—more than ten times the size of Central Park. Even after discounting environmentally sensitive sites like parks and wildlife reserves, the feds own plenty of land in high-potential locations in places like San Francisco, New York, and—of course—Washington DC.

Today’s letter will analyze the potential in federal land from both policy and real estate investment perspectives. Specifically, we’ll tackle:

A brief history of federal land;

Estimates of the opportunity in federal land;

Under-discussed urban sites;

Thoughts on what might happen next.

Let’s dive in.

A Brief History of Federal Land

The federal government is America’s largest landowner, and it’s not particularly close.

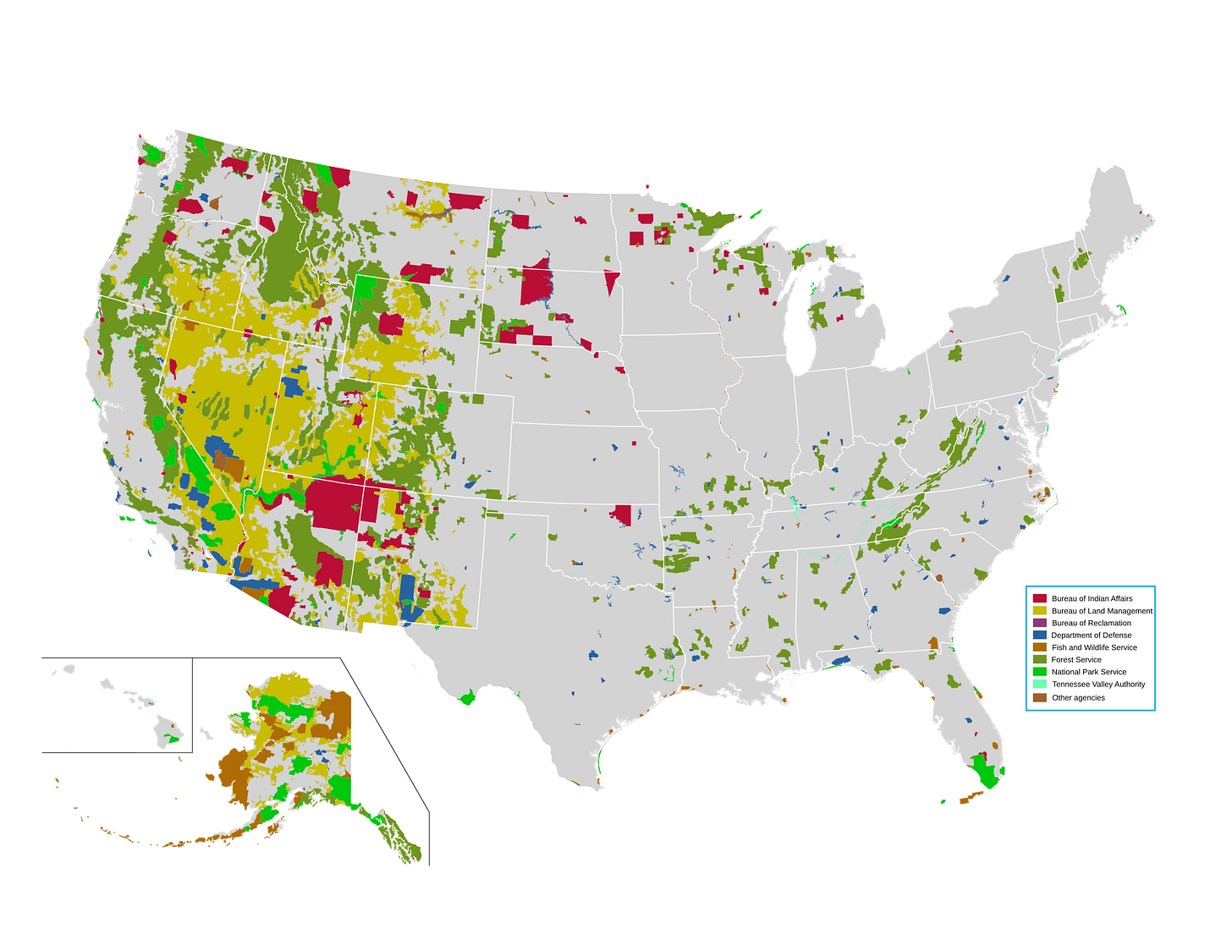

In total, the federal government owns approximately 650 million acres—27.4% of the country—with Native American tribes owning another 56 million acres through the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In total, the US government owns thirty times more land than than the single largest private landowner, the Emmerson family.

Of those 650 million acres, a plurality are held by the Bureau of Land Management, or BLM. Established in 1946, the BLM exists to steward federally owned but not otherwise notable (e.g., parks, national forests, and monuments) land. The majority of BLM-owned land is arid scrubland and desert, so a decent portion of the BLM’s work involves administering grazing leases and mining licenses.

While the BLM is the largest federal land manager, it’s not the only one. The Forest Service, Parks Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Indian Affairs, and Department of Defense each control tens of millions of acres. But even small agencies have significant real estate holdings by private industry standards. The US Postal Service, for instance—which the Trump administration plans to dramatically cut—owns more than 20,000 acres of land across 8,400 sites, many of them in populated areas.

Opening up federal land for housing development isn’t as crazy as it might sound. Unlike, say, annexing Greenland, it’s not a uniquely Trumpian endeavor. Past presidents—including Biden and Obama—have attempted to do more with federal land to solve housing challenges but have largely been stymied by the complexity of it as well as environmental concerns.

And the BLM’s unwillingness to part with land is a relatively new phenomenon. The original Homestead Act—which provided inexpensive land grants to individuals willing to operate their own farms—wasn’t repealed until 1976 with the last land grant happening in Alaska in 1988. That said, homestead grants had become relatively rare after the Great Depression as interest in subsistence farming waned in an increasingly wealthy and industrialized society.

Bleak Land Matters

The vast majority of federal land is effectively useless from a development standpoint. For one, most of it is much too far from civilization to justify housing development. In addition to not having access to jobs, the infrastructure that development requires—roads, electricity, water, sewer—are largely absent from BLM land. And while we at Thesis Driven are generally bullish on the idea of building new cities, choosing to tackle such a project deep in the Utah scrub is playing the game on hard mode.

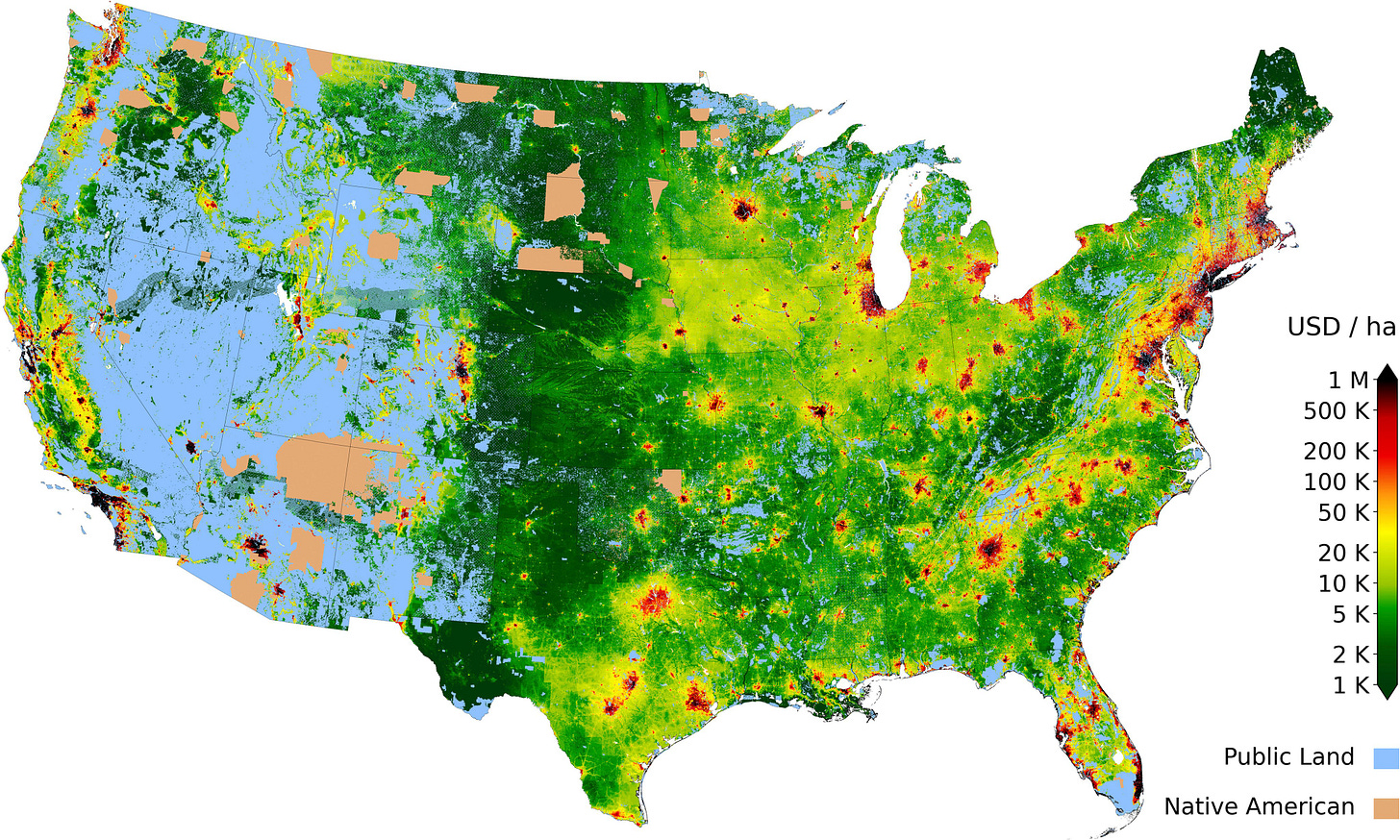

But federal holdings are so vast that even if the great majority of land is useless, there are inevitably diamonds in the rough. Looking at a map of estimated land value illustrates both the problem and the opportunity.

The Wall Street Journal recently estimated that 7.3% of all federal land falls into metro areas that are in need of more homes. While that’s a tremendous amount of dirt—47 million acres—the largest chunks are in relatively rural parts of large “metro areas” that include—for instance—the entireties of San Bernadino County, California and Tooele County, Utah, most of which are inaccessible scrubland far from their parent cities.

But once again, only a fraction of that land would need to be developable to make a meaningful impact on the housing market. American Enterprise Institute estimated that the development of 512,000 acres of federal land—1% of what the WSJ estimated might be viable—could produce 3 to 4 million new homes. The most valuable places for that development would be where blue (public land) touches red and black (high land prices) on the map above, indicating development opportunity. Cities like Las Vegas, Denver, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, and Tucson are likely beneficiaries.

But looking at a map of the entire country can only take you so far. Some of the most valuable federal land sits in the middle of our most expensive cities.

The Urban Opportunity

At the Golden Gate Bridge’s southern terminus is the Presidio, a 1,491-acre federally-owned former military base—and some of the most valuable real estate on the planet.

While beautiful, the Presidio is not untouched nature. It was originally a US Army post and Coast Guard base until being decommissioned in 1990. Today, the Presidio is a mix of old military buildings, offices, forests, a handful of low-rise apartments, and a golf course.

There are any number of reasons why fully developing the Presidio for housing would be unworkable. But even developing half of it—approximately the portion already taken up by low-rise, non-natural uses—at the same density as the rest of San Francisco (18,000 people per square mile) would provide homes for more than 25,000 people. Developing it at the density of, say, Park Slope, Brooklyn, could house more than 100,000 people.

New York City’s Floyd Bennett Field offers a less controversial example of urban federal land that could become housing. A former naval air station in far southeastern Brooklyn, Floyd Bennett Field was a playground for drag racers and RC plane pilots before being turned into a tent city for migrants two years ago. A paved-over, windswept expanse, Floyd Bennett Field has few redeeming qualities today. It should be housing.

If the federal government is serious about downsizing its real estate portfolio to build housing, Floyd Bennett Field is hardly the only example I’d cite. Eight miles to the west sits the 182-acre Fort Hamilton, New York City’s only active military installation. While Fort Hamilton occupies key strategic heights astride the entrance to New York Harbor—and this is not a military publication—it’s possible that artillery batteries on a hill are obsolete in an era of missiles and drones, and the incredibly valuable site would be better used for housing.

Even “small” federal sites have tremendous potential and value as housing developments. The USPS’s Morgan Mail Facility, for instance, takes up two entire Manhattan city blocks in the shadow of Hudson Yards where studio apartments are renting for upwards of $5,000 per month. As I said earlier, the feds own 10,000 acres in New York City alone—enough space for hundreds of thousands of new housing units.

I could go on.

But generally, most of the takes I’ve read on the potential of federal land miss the substantial urban opportunity. Sure, the vast majority of federal land is rural—but the numbers are so massive that even a fraction of the government’s the urban land alone could do a number on our housing shortage.

Doing It Right… or Not

The problem, of course, is that the current administration generally hates cities and loves sprawl. Despite having record-high rents and housing demand, New York City is regularly vilified as a crime-ridden dump in which no reasonable person would choose to live.

To be clear, I’m not one of those urbanists religiously opposed to greenfield development. We make it too hard to build things across the board, both greenfield and infill. Bringing down housing costs demands an all-of-the-above approach: urban infill, incremental greenfield, and perhaps even totally new cities.

That said, I’ll be pleasantly surprised if the Trump administration chooses to direct its energy to unlocking infill sites in urban areas—versus, say, vacant BLM land 40 miles outside of Phoenix.

But even if the federal government does unlock urban sites, they can still find ways to muck it up.

Consider New York City’s Governors Island. A former Coast Guard base, the 172-acre island—a mere 800 yards from the tip of lower Manhattan—was handed over to the City of New York by the federal government in 2003. But as part of the transfer, the feds placed the island under a deed restriction that prohibited, among other things, housing.

In the 22 years since the handover, the City has dithered on what to do with Governors Island. The island was placed under the authority of a nonprofit trust, which has toyed with various uses over the years: glamping, oyster farming, a high school, corporate retreats, and more. The current plan—a climate change research center led by Stony Brook University—aims to begin construction in late 2026. But even if Stony Brook’s plans proceed, the majority of the island will remain undeveloped 30 years after handover.

Wild, undeveloped space can be great. But Governors Island suffers from many of the same problems as the Presidio, sitting in the uncanny valley of activation. There is enough going on there that it’s not really parkland open to all—chunks of space are regularly taken over by events as well as private uses—but there’s not enough happening that there’s always something to do and a reason to go.

More than two decades in, we’d probably all be better off it had just been housing from the start.

The Governors Island tale also illustrates the challenges an aggressive federal government will likely run into at the local level. Even if the Governors Island deed had allowed housing from day one, what was to prevent the City from slow-playing zoning and permitting, kowtowing to local NIMBYs and blocking development? The Governors Island proposals involved the most inoffensive, publicly palatable land uses imaginable, but they’ve still been tied up in indecision for a generation.

Long-term leasing—rather than selling—federal land could help circumvent this, as the federal government would retain control of the zoning and permitting process on land it owns. But that could come at the expense of financeability, as real estate investors and buyers tend to be skittish of leasehold sites.

One of my favorite development stories of the past decade is a case study in how high-density housing can be built on urban land beyond a local government’s control. In the middle of urban Vancouver—a city with a serious housing crisis—the Squamish native nation has jurisdiction over 10.5 acres. Rather than turn it into a museum or some simulacra of ancient life, the tribe decided to use their unilateral control to build high-density rental housing—specifically, 6,000 units and 3.8 million square feet of towers.

It is entirely within Trump’s power to effect similar projects across all of America’s most housing-constrained cities, fulfilling his ultimate destiny as the son of a New York real estate developer. Whether he does it remains to be seen, but the power of federal land shouldn’t be counted out.

—Brad Hargreaves

So, maybe the scientists working to colonize Mars can test-case their habitability scenarios in those areas described as too rural. It would be a magnificent accomplishment to build a new city with proven and cutting edge technologies. “We should do it not because it’s easy, but because it’s hard.”JFK

Agree. My comment was an obtuse double entendre taking aim at the sheer stupidity of thinking someone will colonize Mars when in fact we are having issues -well laid out by you- improving and building new cities on our life-supporting blue marble.