Seven US Transit Projects Real Estate Investors Need to Know

New transit connections have the potential to unlock neighborhoods and fuel new demand. What are the next major projects on the horizon?

Thesis Driven dives deep into emerging themes and real estate operating models. This week’s letter outlines the most important new transit projects being built and planned in the US today and evaluates the real estate opportunities created by each.

Cities are shaped by how people move around them. Even in the most car-dependent markets, new transit routes have the potential to transform a local real estate landscape, creating wealth and opportunities for developers and landowners alike.

In Charlotte, North Carolina—one of the most car-dependent cities in the US—the opening of the Lynx light rail route in 2007 spurred the development of the South End into one of the Sunbelt’s trendiest and fastest-growing neighborhoods, creating an opportunity for dense residential development and retail along the transit corridor. Similar transit projects in the past years have unlocked new development in markets including Los Angeles, Seattle, Northern Virginia, Toronto, and more.

With the Infrastructure Act and Inflation Reduction Act together dedicating over $40 billion dollars to transit projects nationwide, we expect to see even more transformative projects opening in the coming decade. Today we will look ahead at some of the most impactful US transit improvements coming down the pike.

Each project we discuss here will be rated on a highly rigorous scale of 🏗️ to 🏗️🏗️🏗️🏗️ based on its likely impact on the local real estate market. We’ll also opine on specific opportunities that may be created for real estate investors by each project.

Sound Transit Link Light Rail Expansion

Seattle, Washington

Seattle is a notable transit success story—at least by recent US standards. Prior to the pandemic, Seattle had seen steady year-over-year growth in both bus and train ridership, with transit mode share climbing from 18% in 2010 to 23% in 2018. And Seattle is accomplishing this without any legacy transit infrastructure; the city’s first light rail system only began operation in 2003.

But Seattle is hardly done; rather, its transit expansion plans are by far the most ambitious of any US city today. By 2044, the city plans to build 116 miles of light rail connecting 70 stations across five separate lines. While most US metros are content adding a few new rail stations or a bus rapid transit route, Seattle is building an entire transit system from scratch.

Currently, Link light rail relies on one north-south trunk line connecting downtown with the University of Washington to the north and several neighborhoods as well as SeaTac airport to the south. A future expansion will head east to serve Bellevue and Redmond, while another will head north to Lynnwood and Everett. Continued expansion of the trunk line will eventually reach Tacoma to the south, with additional improvements coming on the East side of the city.

Real Estate Impact: 🏗️🏗️🏗️🏗️

Sound Transit is the only project on this list to receive the highest possible score of four 🏗️s. Seattle’s light rail development is taking place at a scale that could not just unlock specific neighborhoods but fundamentally rework the city’s connectivity and travel mode share.

Given the scope of Seattle’s transit expansion, it’s tough to pick a particular area that will see outsized benefits. That said, a railway with good headways into downtown Seattle will surely benefit Bellevue, Redmond, and other eastern suburbs with strong job centers of their own. But the biggest impact of Sound Transit’s expansion will likely be on parking needs city-wide. By 2035, Seattle is likely to have a top-5 transit system comparable to Boston’s MBTA or DC’s Metro—elevating it into the ranks of cities where owning a car is helpful but not necessary for day-to-day life and making parking a mere nice-to-have in a significant portion of the city.

The Interborough Express

Brooklyn and Queens, New York

While the Second Avenue Subway draws the lion’s share of the attention when it comes to NYC transit expansion, the Interborough Express will likely be far more impactful and interesting from a real estate standpoint.

While NYC is a transit town—58% of New York metro area commuters travel via mass transit—travel options between outer boroughs is remarkably poor. In many cases, the fastest route between Brooklyn and Queens includes a trip into Manhattan, a legacy of the region’s historic Manhattan-centric development and mindset.

The Interborough Express intends to fix that. By using an existing freight rail right of way, the Express will connect 17 different subway lines and the Long Island Rail Road while running 14 miles from Bay Ridge, Brooklyn to Jackson Heights, Queens. Current plans call for five minute headways during peak times, comparable with other NYC subway lines and far superior to the other transit projects featured here.

Real Estate Impact: 🏗️🏗️🏗️

Once complete, the IBX will dramatically increase connectivity for a wide swath of Brooklyn and Queens neighborhoods, including many—like East Flatbush, Canarsie, and Maspeth—that haven’t seen the new development of the past two decades of neighborhoods like Crown Heights and Bushwick.

Furthermore, the Express is a step toward the decentralization of New York City, making businesses and offices headquartered in the outer boroughs more viable. Having an office in Jackson Heights or East Broadway may be less absurd once those locations can easily draw from employees across Brooklyn and Queens.

FrontRunner Double Tracking

Front Range, Utah

Earlier this year, the Biden administration budgeted $316 million to “double-track” FrontRunner, the commuter rail line of Utah’s Front Range. FrontRunner connects cities including Ogden, Salt Lake City, Lehi, Orem and Provo.

Double-tracking a commuter rail line offers benefits to efficiency, capacity, and reliability. With double tracking, FrontRunner plans to upgrade from 30 to 15 minute headways, meaning trains are only 15 minutes apart during daytime hours. While this may not seem like a transformative improvement, a 15 minute headway means that people can take the train without needing to look up a timetable in advance, totally changing how commuters and visitors alike can use transit.

Real Estate Impact: 🏗️🏗️🏗️

Utah has been the fastest-growing state in the nation for years, and FrontRunner connects Utah’s largest cities. With 15 minute headways, FrontRunner will make living in downtown Ogden or Provo while working in Salt Lake City (or the reverse) far more viable. Expect to see continued infill development in downtown areas along the Front Range in the coming years.

Brightline Expansion

Florida

No US transit project has garnered more attention and hype over the past decade than Brightline’s launch in Florida. Today, America’s first new private intercity rail line built in more than a century connects Miami to West Palm Beach via Fort Lauderdale and Boca Raton. And earlier this year, Brightline turned its first profit ever.

Unlike many public transit projects, Brightline offers travel times competitive with private cars: 30 minutes to Fort Lauderdale and 72 minutes to West Palm Beach. And the headwinds facing other transit agencies don’t seem to be impacting Brightline; the service continues to post record ridership numbers.

Starting in September, Brightline will run trains to Orlando International Airport. With a max speed of 125 miles per hour, Brightline will be able to make the Miami-Orlando trip in three hours, faster than a private car and comparable to plane travel once other hassles like security are taken into account. And Brightline is considering further expansions to Tampa and even Jacksonville.

Real Estate Impact: 🏗️🏗️

Brightline’s success and expansion is surely a good thing for Florida, and I hope it can be an example for other urban clusters poorly served by transit today (for example, the Texas Triangle).

Real estate opportunities will surely arise near Brightline stations and in smaller towns served by Brightline such as Stuart and Fort Pierce with proposed stops along Brightline’s Orlando route. But Florida doesn’t have great connecting transit infrastructure; the state has historically under-invested in light rail, buses, and other options that would help people get from Brightline stations to their final destination. And with 60 minute headways, Brightline is far from serving as a commuter rail system. This will be a headwind to true transit-oriented development near Brightline hubs.

Project Connect

Austin, Texas

Austin’s plans for mass transit have seen many fits and starts, but plans may be finally coming to fruition. The Austin Transit Partnership recently revealed the proposed route for the city’s new light rail system after voters approved a property tax increase to fund the construction of the system in 2020.

On the north end, the light rail would connect with buses and park & ride at the North Lamar Transit Center. From there, it would connect with UT Austin and downtown before crossing the river and heading east toward the airport. Officials estimate it would serve 28,500 riders per day, which would make it the 10th most popular rail transit system in the country behind Miami’s Metrorail. This would also be a third of MARTA’s Atlanta ridership and 0.47% of the New York City Subway for those keeping score at home.

The project has faced substantial headwinds from the State of Texas, which has been historically hostile to mass transit and has constitutional provisions forbidding the state from using gas and vehicle registration tax revenue for anything but roads and highways.

Project Connect’s current vision also has substantial flaws. One, the light rail line isn’t grade-separated for the majority of its length including the critical stretch through downtown. This decreases the speed at which trains can run and increases the likelihood of them getting stuck behind cars. Project Connect is also expected to cost at least $11 billion—or $285 million per kilometer—a hefty price tag for at-grade light rail.

Real Estate Impact: 🏗️ 🏗️

Before commenting on Project Connect specifically, it’s important to note that Austin has the most new homes under construction per capita of any US metro area, and it’s not particularly close. Even with Austin’s substantial population growth, the market will take some time to absorb all those new units.

But Austin’s increasingly horrific traffic—and the lack of alternative travel options—is likely the greatest threat to Austin as a viable city. Any commitment to a major investment in transit—even a flawed one like Project Connect—is ultimately a good sign for the city and represents an opportunity for developers looking to build near transit stations. But it may take some time to work through the current apartment supply.

Metro Purple Line Extension

Los Angeles, California

Despite being a bastion of car culture, Los Angeles has embarked on an aggressive transit expansion plan. The Regional Connector—the longest light rail line in the world—opened earlier this year, connecting Long Beach to Azusa and the San Gabriel Valley. It builds on the successes of the Expo line which opened a decade ago to connect Santa Monica and the west side to downtown LA.

Los Angeles’s next transit expansion will run a few miles to the north of the Expo line, connecting Westwood and Beverly Hills to downtown Los Angeles through Hancock Park, Wilshire Center, and K-Town. The Purple Line Extension serves transit-starved, (mostly) mid-rise neighborhoods along Wilshire Boulevard.

The LA Metro’s expansion is not without its challenges. One, the city has resisted attempts to allow higher density development near rail stations, starving the system of passengers and limiting transit’s effectiveness. And Los Angeles’s transit system has also been plagued with crime, disorder, and homelessness, problems that have likely dissuaded riders from embracing Metro’s new transit options.

Real Estate Impact: 🏗️🏗️

From a real estate perspective, the Purple Line isn’t exactly serving neglected neighborhoods; over the past decade the west side of Los Angeles has seen considerable investor interest—and rent increases—that have little to do with pending transit improvements.

That said, there is reason to be optimistic about the region’s transit writ large; other expansions including the Sepulveda line and the Inglewood Transit Connector will have a compounding effect on the usability of LA’s transit system.

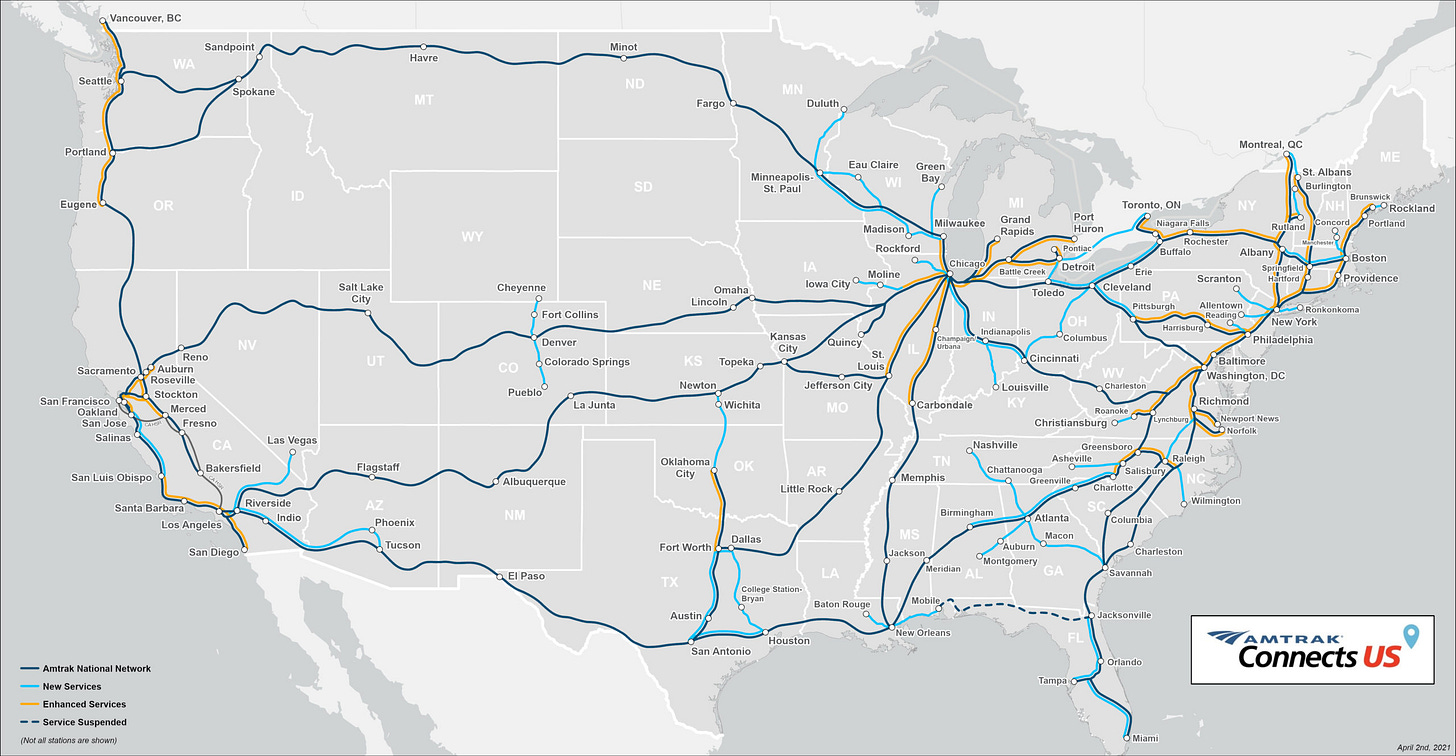

Amtrak Expansion

Nationwide

Flush with cash from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Amtrak has embarked on its most ambitious expansion plan in decades: a $75 billion investment in creating or upgrading dozens of lines. This includes new connections to a number of cities not currently served by Amtrak at all.

Currently, Amtrak’s passengers are concentrated in a few places; more than half ride along the Northeast Corridor with meaningful numbers also traveling between San Diego and Los Angeles as well as Portland and Seattle.

Unfortunately, many of the new branch lines added won’t be competitive with car travel from a time standpoint; an analyses of new routes showed that many added more than an hour—if not more—to travel times. Since Amtrak doesn’t own or control most of its tracks outside of the Northeast Corridor, Amtrak passengers are often left waiting on freight trains to pass, adding significant delays to train trips and making them broadly uncompetitive with other forms of transportation.

Real Estate Impact: 🏗️

The biggest winners here will be the affordable tertiary cities that gain easier access to cities in which rail travel is already prevalent. A one-seat Amtrak ride from Penn Station to Scranton, for example, seems likely to draw more weekend travelers and even some commuters who work from Manhattan a day or two per week.

Concord (NH), Allentown (PA), Reading (PA), and Rockford (IL) all seem like likely beneficiaries of this phenomenon. Other cities slightly farther afield but with strong natural amenities—say, Christiansburg (VA), Asheville (NC), or San Luis Obispo (CA)—will likely benefit as well from being more viable long-weekend destinations.

I am much more skeptical that marginal (1-2x per day) train service will be of much benefit to smaller cities in regions where train travel is the domain of grey-haired tourists and aerophobics; it would be a stretch to believe that a once-daily eight-hour train connection to Oklahoma City will drive much economic benefit to Wichita, for example.

—Brad Hargreaves