Where Are the New Cities?

The past decade has seen a resurgence of interest in the creation of new cities. But where are they actually getting built?

Thesis Driven dives deep into emerging themes and real estate operating models by featuring a handful of operators executing on each theme. This week’s letter is on the creation of new cities.

There is no domain of real estate investing as ambitious—or insane—as the creation of new cities. Between the massive amount of capital required to achieve critical mass and economic viability and the long list of past failures, there is good reason why most real estate LPs stick to investing in well-established metropolitan areas.

That said, more new cities have been created over the past several decades than most of us may realize, including several in the United States. And over the past decade, three macro trends have led to renewed interest from many in the creation of new urban areas.

One, remote work has untethered more knowledge workers from existing cities, lowering the economic cost of “trying out” a new place.

Two, the flaws of existing cities—often some combination of housing shortages, decaying transit, homelessness, and crime—have gained prominence and attention, driving some respected entrepreneurs and investors to propose the creation of new cities.

Three, the rise of “placemaking” as an attractive real estate investment thesis—think DUMBO or Reston Town Center—offers a stepping-stone for ambitious real estate investors.

Today I’ll attempt to categorize the current major attempts to create new urban hubs. This is not meant to be a how-to guide for people who would like to build their own new city—there are plenty of those out there, surprisingly enough—but rather a sector overview covering the major players and trends, as we did with OpCo-PropCo models several months ago.

While large urban expansions such as Masdar City and Songdo IBD are interesting—and often raised in the same discussion as new cities—they are nonetheless extensions of existing metro areas and aren’t considered here. Nonetheless, the precedent they provide is instructive to educating investors and lenders on pushing the geographic boundaries of viability.

To structure this overview, I divided all current attempts to create new cities into three broad categories: Autocratic Ambition, Utopianism Writ Large, and Capitalism at Work. There are areas of overlap between these, but they broadly encompass the city-building models we see at work today. In each category, I’ll pick a few representative examples of new cities and will score each on four metrics:

Ambition (one to four 🧠s). Does the project present a vision for something new and different, or is it simply a suburb or extension of an existing metro area?

Urbanism (one to four 🚇s). Is the project committed to good city-building principles? Are the creators building a place one might actually want to live?

Oppression (one to four 🪚s). As we’ll see, many new cities are being built by regimes with less-than-stellar human rights records. New metros from more autocratic governments—often making data collection a top priority—are indicated by more bone saws.

Seriousness (one to four 🏗️s). Is this city actually going to get built? Is the project capitalized and entitled, or will this sit forever on an architect’s website?

Autocratic Ambition

The easiest way to start a new city by far is to run a less-than-democratic country and create the city by fiat. The majority of new cities under construction today are projects of state creation, although many have significant private-sector engagement across architecture, design, construction, and economic development.

In general, national leaders create cities for a few reasons. Most often, they do so to move their national capital and critical government functions out of a large, dense, hard-to-control city to somewhere more revolution-proof. But new cities as national projects can also be driven by some combination of personal vanity, economic development, and national pride.

The Line | Saudi Arabia

The Line is the flagship city of Neom, a large special economic development zone on the Red Sea coast of Saudi Arabia. Perhaps the most well-known new city under development today, The Line is a 110-mile long, 660-foot wide “linear city” designed to have no streets or cars. Instead, a high-speed rail line will run the length of the city.

While many have written The Line off as a pipe dream, recent drone footage shows excavation and construction work well underway. The total cost is expected to be somewhere between $100 billion and $1 trillion, a wide range appropriate for such a novel and ambitious project. A litany of prestigious architects and consultants from the US and Europe and have been retained for the project, which has been criticized for everything from its environmental footprint to its humanitarian impact on local tribes.

Ambition: 🧠🧠🧠🧠

Urbanism: 🚇🚇

Oppression: 🪚🪚🪚

Probability: 🏗️🏗️🏗️

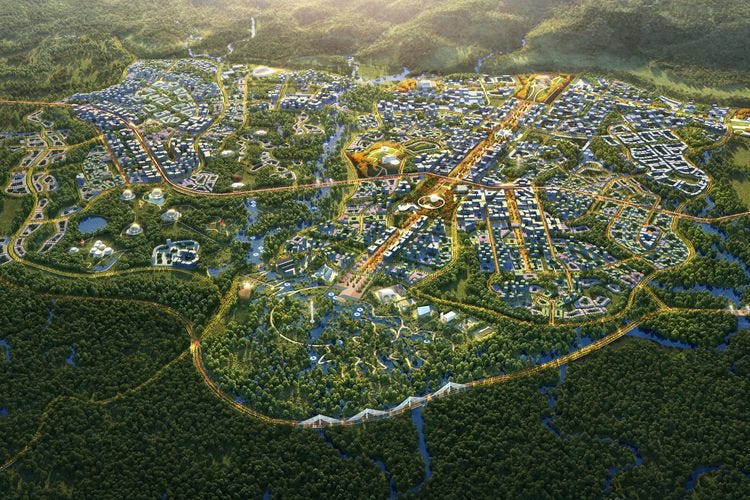

Nusantara | Indonesia

Construction work began in July 2022 on Nusantara, which will be the new capital of Indonesia upon its planned inauguration in 2024. The city will replace Jakarta, the current capital, which suffers from some of the worst traffic in the world and also happens to be sinking into the ocean.

Located on the eastern coast of the island of Borneo, Nusantara’s design came out of a competition held in 2018. Sustainability—specifically, avoiding Jakarta’s car-dependence—was a key criteria in the selection process, and the Indonesian government estimates that 80% of trips in Nusantara will happen by public transit.

Ambition: 🧠🧠

Urbanism: 🚇🚇🚇

Oppression: 🪚🪚

Probability: 🏗️🏗️🏗️🏗️

New Administrative Capital | Egypt

Egypt’s new administrative capital is being built for one primary reason: to avoid another Tahrir Square 2011 event by moving the government outside of central Cairo—specifically, 28 miles to the east.

Under construction since 2015, the new capital is nothing if not ambitious. The government’s plans include constructing the world’s tallest tower, a 1,000-meter structure that would surpass the Burj Khalifa in height. Unfortunately, the new capital’s design—with wide boulevards, broad setbacks, and limited mass transit—replicate many of the mistakes made in previous capital city-building projects such as Naypyidaw (Myanmar) and Brasilia (Brazil).

Ambition: 🧠🧠

Urbanism: 🚇

Oppression: 🪚🪚🪚

Probability: 🏗️🏗️🏗️🏗️

Utopianism Writ Large

The desire the create a different world—to rewrite the rules of government, finance, and society—has been the primary driver of new city formation for centuries. From Josiah Warren to Brigham Young, the United States in particular has a strong tradition of utopianism often driven by extreme commitments to religion.

As we will see as we look at current examples, not all utopian models are divinely-inspired. Instead, many are driven by a desire for freedom from sclerotic local regulations and the glacial pace of infrastructure development. While "we can build bike lanes and 5-over-1 apartment buildings” may not sound like compelling millenarianism, it is nonetheless a breath of fresh air for city-dwellers struggling with the impacts of bad governance on urban housing prices and transit.

Telosa | possibly Nevada, USA

Telosa is the brainchild of Marc Lore, an e-commerce entrepreneur. He plans to create a city of five million based on Georgist principles with all land held in a foundation supporting the improvement of Telosa’s infrastructure as well as “increase the happiness and wellbeing of Telosa’s citizens.”

Upon its announcement in 2021 with glossy renderings and a Bjarke Ingles-designed cityscape, Telosa generated significant criticism, with many arguing that the city’s initial plan of locating in the Nevada desert would further strain already-limited water resources. Since, Telosa has revealed that they are investigating a wider list of sites, including one in the Appalachians. The status of the project today is unclear; the City of Telosa only has six employees on LinkedIn, most of whom appear to have other jobs as well.

Ambition: 🧠🧠🧠🧠

Urbanism: 🚇🚇

Oppression: 🪚

Probability: 🏗️

Praxis | TBD

Perhaps the most serious of the US technology community’s efforts to build their own city, Praxis is backed by an interesting list of investors ranging from 8VC’s Joe Lonsdale to Opendoor’s JD Ross to perennial New York Republican figure John Catsimitidis. Their master plan takes a thoughtful approach and is available for anyone to read on their website. Their lack of absurdly over-ambitious renderings also compels to me award them two 🏗️s worth of probability.

Ambition: 🧠🧠🧠

Urbanism: ?

Oppression: ?

Probability: 🏗️🏗️

Kiryas Joel (“KJ”) | Orange County, NY

By many metrics, Kiryas Joel is the most impressive new city built in the United States in the past two generations. It’s fairly large and fast-growing, with 35,000 or so inhabitants and gaining 3.6% per year. It has also achieved a population density comparable to New York City with over 22,000 people per square mile across dense low- and mid-rise apartment buildings and a robust local bus system.

Of course, KJ is also the poorest zip code in the United States with over 70% of residents below the poverty and a median age under 12. As an enclave of the Satmar sect of Orthodox Judaism, KJ reflects a different sort of utopianism than the other cities in this category and is—to say the least—highly controversial. I’d recommend anyone looking to learn more check out the recent book American Shtetl by Nomi Stolzenberg and David Myers.

Ambition: 🧠🧠🧠🧠

Urbanism: 🚇🚇🚇

Oppression: 🪚🪚🪚

Probability: 🏗️🏗️🏗️🏗️

Capitalism at Work

The final category of new cities eschew the language of utopianism entirely. While they may be ambitious, these urban ventures are by-and-large capitalist enterprises intended to make money for the principals and their investors.

Crypto Cities | Various, but usually the desert

This is a catch-all category for the various attempts from cryptocurrency investors to create new cities. At the height of the crypto craze in 2021 and 2022, the sector saw numerous proposals from newly-wealthy investors to build startup cities—including a few that went so far as to acquire land.

Crypto investors are likely to be aspiring urban entrepreneurs for a few reasons. One, early crypto investors—often the ones who made the most money—usually decided to get into the sector because they were skeptical of existing financial and government institutions, so there’s natural appeal in creating new ones. Two, the ability to influence regulation and tax law by creating a new jurisdiction is compelling to people who just made a giant pile of money on the fringes in finance.

Now that crypto prices have cooled across the board—and the DAO governance structure has lost some steam—I am skeptical any of these will see the light of day.

Ambition: 🧠🧠🧠

Urbanism: 🚇

Oppression: 🪚

Probability: 🏗️

The Villages | Florida, USA

With over 80,000 residents, The Villages is the largest 55+ age-restricted master-planned community in the United States. Founded in the 1960s by an entrepreneur selling mail-order homes, the Villages recently saw significant expansion, growing by 54% over the past decade. Today, The Villages offers over a hundred recreation centers across 13 separate community governance districts. It’s also a frequent stop for US Presidential candidates.

The Villages is notable for sticking to its mail-order roots, with prospective buyers offered a limited and constrained selection of designer homes to build or buy off the shelf. Like its housing stock, The Villages’ population is not particularly diverse: it’s 98% white with a median age of 67, the highest in the US.

Ambition: 🧠🧠

Urbanism: 🚇

Oppression: 🪚

Probability: 🏗️🏗️🏗️🏗️

Different stakeholders will see distinct opportunities in each category of new cities. New capitals in autocratic regimes are unlikely to be compelling to real estate investors or entrepreneurs but are very lucrative for architects, designers, and consultants. Similarly, ambitious neo-utopian concepts are unlikely to appeal to real estate investors more eager to bet on tried-and-true models.

Autocratic fiat aside, new cities are successful if they can make a clear economic case to prospective residents at every stage of their development. Good weather and thoughtful urban design are positive things, but those aren’t the factors that compelled tens of thousands of people to move to western North Dakota ten years ago. They came for money, and they left just as quickly when oil prices dropped and the money dried up.

Ski resorts are perhaps the best examples of new “cities” with more sustainable natural advantages. Summit Series’s foray in Powder Mountain, Utah a decade ago offers one of the more interesting examples of translating a pre-existing community into a greenfield real estate venture. “A ski resort that actually builds workforce housing” may not be the most ambitious pitch for a new city, but it’s perhaps the most likely to succeed financially. A good slope will bring tourist dollars, forming a sustainable basis for a new city even at a small scale. Boyne Resorts’s development of Big Sky, Montana follows a similar—albeit more traditional—path.

Ultimately, real estate investors and entrepreneurs interested in tacking the development of a new city may be served well to think less like tech entrepreneurs—with a bias toward from scratch—and more like private equity entrepreneurs, identifying a natural asset or location with compelling fundamentals suffering from neglect or mismanagement. Vision, quality management, and pre-existing community—the things innovators can bring—may see the best return applied to a neglected ski resort rather than a stretch of empty Nevada desert.

yours,

Brad

I'm sad by how short this list is. And how low probability the projects are (I generally agree with your assessments).

We seemed to have lost the ability to create new places. And therefore our ability to experiment on better ways of living, governing, and coordinating human activity has suffered.

None of the 10 most populous cities in the US were founded in the last 150 years. Our youngest city - Phoenix - was founded in 1868 and that was the same year as the first underground railroad and the French still occupied Mexico.

We've inherited our cities from a distant and unrecognizable past. We are governed by ghosts from a forgotten era.

I wonder if we can dispense with the utopian undertones here and set our sites on just creating new places that are moderately better along some dimensions for a specific group of people. The Villages seems like the project most in this spirit and I wouldn't want to live there personally, I like the intentionality and resident-centricity of the approach.